by Susie Campbell

Introduction

The wastelands of this book are places of elusive meaning, of absence and unexpected presence, of decay and also of becoming. They sit at the intersection of the internal and the external, and they can be places for encountering the uncanny. They are environmental, existential, and linguistic, and include literal waste in the form of an actual landfill site. The retrieval of waste materials from this site– helped by my dog, rescue hound Charlie - and the making of ritual objects and costumes from this literal rubbish helped me to explore the deep interconnections of these different ‘wastelands’ and to develop a ‘waste poetics’ for the book.

This wastelands project began as an engagement with what lies beyond the bounds of the Pilgrims’ Way, which according to the Ordnance Survey traverses the Surrey Hills on its way from Winchester to Canterbury. In fact, this is largely mythological and due to the work of a Victorian OS surveyor who unified multiple pilgrim paths, drove roads, and ancient trackways into a single Way. Nineteenth century iconography romanticised and celebrated this idealised Pilgrims’ Way but rendered everything else in the location, including its diverse networks of prehistoric pathways and sacred sites, as an empty ‘wasteland’. While the Pilgrims’ Way itself is famed for its walks and its ‘heritage’, what lies to either side is stripped of value: first exploited for industrial extraction then used for landfill.

Of course, in Western mythology, wastelands have come to be associated with a wounded king or priest, a figure whose mysterious connection to the land means that the injured, impotent, or mutilated body of the former is manifested in the waste of the other. My fieldwork and other developmental processes for this project brought home to me how much this also works the other way round. The mutilation of the land results in our own wounding. The inner ‘wastelands’ of ecological numbness and ethical despair may spill out into a depleted natural world, but the devaluation, exploitation and destruction of the environment may spread inwards, breaking down any neat divisions between ‘internal’ and ‘external’, revealing instead a highly charged, unpredictable psychic and physical entanglement. How to navigate and map such enmeshed wastelands was the starting point for my Wastelands project. The purpose of this essay then is to share some of the book’s exploratory processes but also to signpost to some of the project’s associated performances, poetic rituals, material objects and research. I start with a discussion of the project’s different archaeologies – waste, rescue, and canine – and then reflect on its quieter, archival aspects.

Textile waste recovered during my fieldwork

‘Waste Archaeology’ in the making of Wastelands

There are two ways in which archaeology has been important to my Wastelands project (building on my previous Guillemot Press publication The Sleeping Place, with artwork by artist/archaeologist Rose Ferraby, which explored an archaeological approach to poetry). One of these ways is the ‘rescue’ archaeology which uncovered vital evidence of Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age settlement at what is now a landfill site, even as the site was being destroyed by quarrying. I will be discussing this below. However, much of my project fieldwork involved excavating waste items protruding from the surface of my local landfill site and so this piece attempts to contextualise these finds within the context of ‘waste archaeology’.

Of course, middens, debitage, and shards of all kinds play a hugely important role in archaeology. What I am discussing here is the study of more recent trash deposits which would not perhaps usually be considered as ‘archaeological’. Matt Edgeworth (‘An Anthropocene Section’ in Contemporary Philosophy for Maritime Archaeology, eds. Sara A Rich and Peter B Campbell, Sidestone Press, 2023) argues that the ‘archaeosphere’ – that is, human-modified layers of ground – can be considered ‘archaeological’ whatever its age. Edgeworth carried out his investigations at a riverside landfill site next to the lower reaches of the River Thames, treating the mass of waste exposed by tidal surges (due to rising sea levels) as a ‘section’ through the archaeosphere, exposing technofossils, plastics, bottles, and a ‘ticking time bomb’ of dangerous materials newly exposed or polluting the water. I had already completed most of my fieldwork at my landfill site by the time I came across Edgeworth’s work (thanks to a timely signpost from Professor Clare Brant) but his findings resonated strongly with my own explorations.

With the help of Charlie Dog (and the unknown foxes and rabbits whose diggings assisted in the recovery of some of the waste materials) I picked up many items of waste similar to those described by Edgeworth: plastics, construction materials, glass, and of course, textiles. I tried to inventory them as though they were ‘finds’.

Most disturbing were the strange technofossil-type amalgamations of man-made and natural materials, plastic fusing into tree roots or moss and grass growing through plastics and textiles.

Plastic waste with growing plant shoots

Edgeworth describes how his landfill site has been made unstable due to tidal action, but I found that this instability is also due to the waste materials themselves, leaking volatile gases and liquids, and seemingly jostling their way back to the surface as the earth shifts around their turbulence and of course helped by rainfall and animal activity. (Of course, from a new materialist point of view, the liveliness of waste exemplifies the instability and entanglement of the whole material world). This discovery was to have a profound influence on my poetics for Wastelands and my interest in how to respond to this material activity and agency.

Hairnet, facemask, and gloves - all part of the poet’s kit!

I laughed grimly when I saw a picture of Edgeworth at work on his landfill, of course appropriately dressed in protective gear. It took several rashes on my skin and a kind lecture from poet Anna Reckin to realise the hazardous nature of what I was doing – hence the following picture of the poet at work!

Another piece of research that resonated strongly with my own is by Jonathan W Gardner, and in particular, his discussion of what makes a wasteland (‘What Makes a Wasteland’, University of Edinburgh, November 2023). Gardner has been undertaking an archaeology of urban wastelands, asking how they are made and examining the effects that this labelling has on how these sites are valued and used. One of the drivers for my Wastelands project was my response to the ways in which value is distributed across certain landscapes, dividing it into mutually constituting ‘waste’ (or ‘empty’) sites, and sites replete with worth. Although the sites I explore for this project are local, this is of course a global issue and is deeply entangled with colonial ways of thinking about the land. And so, I was fascinated by Gardner’s conclusions that the meaning of ‘waste’ at his sites is socially contingent, and often part of a process of devaluation as preparation for particular kinds of exploitation. This resonated strongly with what has been my own intuition: that the notion of waste and wastelands is closely connected with the historical justifications for enclosure of the commons, globally with colonial exploitation in the name of ‘development’, and is still part of a contemporary rationale for industrial and ‘developmental’ exploitation.

Gardner also refers in passing to Adam and Eve’s expulsion into the wastes beyond Eden, a ‘fallen’ landscape, which segues neatly into some of the broader ways in which I consider ‘wastelands’ within my collection.

My initial creative responses to this waste archaeology were several material practices, inspired by the large amount of textile waste I discovered. Textiles, and their intertextuality with written text, have become a vital part of my creative practice. As I embarked on Wastelands, I was already beginning to tease out formal poetic strategies inspired by the loops and knots of hand knitting, a material practice deeply inscribed in the places of this book. It was shocking to me when my fieldwork brought me into direct contact not just with landfill waste, but with significant amounts of domestic and industrial textile waste. Indeed, my first indication that I was standing on a closed rubbish tip was finding long strands of rotting fabric poking out of the ground. This of course is a local manifestation of the massive global problem of textile waste. (For important information (and campaigning) about this issue, see Wendy Ward’s Substack).

I realised that I needed to find a creative response to this discovery, and to find ways to work these waste textiles into my project. Charlie was already digging excitedly at the rotting material. Perhaps I should have stopped him: I helped him. Then I carried home handfuls of the sodden, dirt-encrusted strips of recovered fabric. The loose weave of what turned out to be the backing fabric of an old carpet suggested bandaging, binding, even gagging.

Wound (short film)

My first response to this was a short film ‘Wound’ exploring further my sense of how the mutilation of the land results in a mutual wounding. I made this film in collaboration with independent film-maker (and my niece) Hen Campbell. The film was premiered at the Runnymede Film Festival 2024, and although it is not part of the Wastelands book as such, the film was a vital developmental step in my process. (The book which appears in the film is Hilaire Belloc’s The Old Road, discussed below, and the featured passage is Belloc’s account of walking through the area which is now landfill). The link to the film (7 minutes) is here.

Susie performing ‘Litany’ at Jeannie Avent Gallery. Artworks by Sylee Gore and Nic Stringer, April 2025. Photograph by Sylee Gore

Litany (performance piece)

A second creative outcome was a short performance piece called Litany. This piece uses recovered waste fabric (or its safer proxy, a surgical bandage) as a gag in order to distort and sonically erase some of the language used in the ‘schedules of permitted waste’ that are part of the landfill’s licence. I am grateful to JD Howse and Cat Chong, editor and guest editor of Permeable Barrier, for publishing this sound piece in recent issue ‘Signals’.

My performance included an invitation to the audience to contribute their own rubbish! Other audiences have also given me their litter to take home. This accumulation of donated litter has become the basis of for another performance project: WasteCoat.

WasteCoat

John Leech’s illustration of Marley's Ghost for Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, 1843

From the bags of collected litter from my previous performances, I am making a performance garment to wear at some of the launch readings of Wastelands. I was inspired by Dickens’s description of Jacob Marley’s ghost in A Christmas Carol as weighed down by a heavy chain of his own making: ‘It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel’. It is a chain wrought of greed, miserliness, and a concern for money and profit above everything else.

The ‘chains’ on my WasteCoat are made of plastic bottles, drinks cans, waste fabrics, printer ink cartridges, food wrappings and so on. I remembered how as a child I used to make kite-tails out of paper screws tied on string and this became the basis for my waste chains.

Susie performing with the WasteCoat, picture by Camilla Nelson

The base of the coat is an old coffee sack donated by friend and poet Martin Wakefield with a collar of old gift ribbon, buttons made of mince pie foil cases, and a Pepsi can for a toggle. My thanks to all the audiences who donated this litter. (The Coat includes some empty chains for more waste to be added in the future).

In Wastelands itself, this textile waste takes on a new importance within poetic ritual in the sequence Dog Pilgrim, and the visual poetry sequence Hodening. A further sequence Waste Poetics revisits and ‘recycles’ the language used in the Environment Agency’s schedules of ‘permitted work’. The bureaucratic language of these formal ‘schedules’ works hard to suggest the landfill waste is inert and safely contained in separate ‘cells’. Waste Poetics makes this language work differently to suggest something very different:

Rescue Archaeology in the making of Wastelands

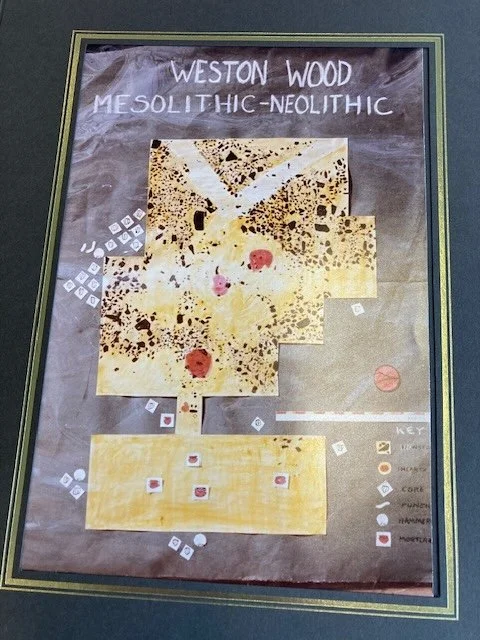

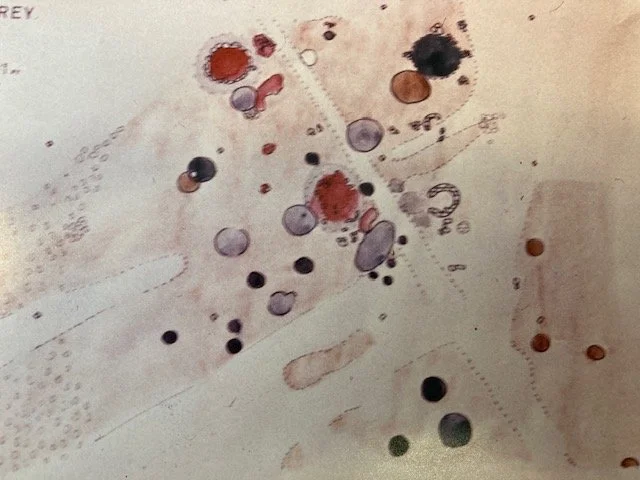

One of the site plans for the rescue excavations

In the early 1960s, as commercial sand extraction ate away at Weston Wood, one of the places explored in Wastelands, a small team of archaeologists and local volunteers did their best to excavate and salvage crucial evidence that this configuration of wooded hills, valleys, springs and wells had been the site of several important prehistoric settlements. This was a desperate and doomed attempt to recover vital archaeological evidence of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age settlement before it was quarried away and buried under waste.

Postholes, pottery shards, quern stones, and burnt grains were mapped and recovered just ahead of the bulldozers. The lead archaeologist was a retired librarian, Joan Harding, and I am grateful to the Surrey Archaeological Society for allowing me to access the archive of her work, and for copyright permission to quote from it in the book. Her letters are a tough read as she desperately pleads for funds and tools to carry out the excavation with little time granted to carry it out.

The bulldozers did not cease their work, and Harding lost her appeal for more time. Her letters speak bitterly (and with uncanny prescience) of how the Duchess of Northumberland (landowner of this site) had hoped the excavations would uncover treasure, beautiful artifacts to display in a cabinet, and lost interest when all she could see was ‘rubbish’: broken quern stones, fragments of pot, and shadowy stains on the ground which was soon to be filled with local waste. The archaeological finds were packed away in paper bags, Harding noting their details on used library index cards, ‘recycling’ them to record vital archaeological data. Then the bulldozers took over, the hillside disappeared, its contours extracted from an ancient landscape with its meaningful and perhaps sacred configuration of burial mounds, standing stones, and a spring known as ‘scír’ for its shining waters. Lost, and then reformed out of waste, as the now-hollow hill was refilled with tons of local rubbish, a new mountain of landfill replacing the old hill which was renowned in local folklore as a place for dancing around the mound at its summit.

A ritual place now lost beneath waste. And so, new poetic rituals seemed an important way to reconnect with this mutilated but emergent old-new place. In my previous Guillemot Press book The Sleeping Place, poetic ritual (referencing the important work done on ‘(Soma)tic Poetic Rituals’ by CA Conrad) was an important way of responding on a different level to the ancient burial site I was exploring through poetic constraint and a restaging of its archaeological history. In the current project, ritual has been crucial as a way into charting what is no longer there, or is re-emerging in some new form. In fact, as the book tells, the whole project started with a ritual which nearly went disastrously wrong – but I will leave you to discover that story in the book itself! As literal waste intruded itself increasingly into my poetic exploration of what I was finding to be a profound meshing of existential, linguistic, and ecological experiences of ‘wasteland’, I found myself drawn further into creating ritual objects and practices out of the recovered waste materials, teasing the abject into the ceremonial and performative. This is explored further in Wastelands’ ‘Hodening’ sequence.

Preparing a ritual object using recovered textile waste, bone, heartwood, gold wire

Recycling

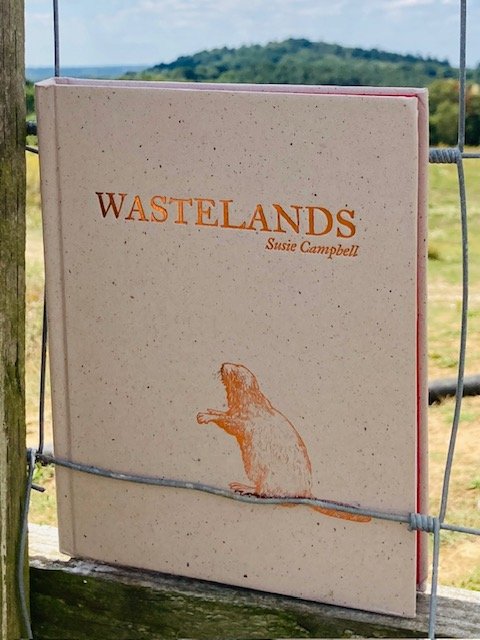

I took the book out to the landfill site and photographed it against the landscape out of which it arose

Throughout Wastelands and these ritual practices I gesture to the kind of literary and linguistic ‘recycling’ alluded to by Harryette Mullen’s great work Recyclopedia (Greywolf Press, 2006) as well as to Harding’s actual recycling of her library cards. Shredded remnants of Chaucer, TS Eliot, Lewis Carroll, Hilaire Belloc and many others are threaded through the text or are patched into new texts. But here I also want to celebrate and draw attention to some recycling that is a meaningful part of the material book itself. The book uses several different papers for its beautiful cover, stunning endpapers, and clean inner pages, all reflecting the publisher’s careful choice of papers which are right for this project, not only because of their look and feel, but also because they come from eco-friendly ranges which use various kinds of recycling and sustainable processes.

The cover of the book, in particular, reflects Guillemot Press’s commitment to sustainable practices as well as editor Luke Thompson’s passion for the beauty of paper, using Favini Crush Cacao, a gorgeous, pale cocoa-coloured paper with chocolatey flecks, made from the residue from chocolate production. The Favini Crush paper range uses the process residues from various organic products to replace up to 15% virgin tree pulp and to draw attention to how these residues might be used rather than discarded as waste. The cover of Wastelands is everything to me: its design, the alert posture of its dextrous little engraved beaver, its tactility, its glorious foil detail – and its engagement with waste as part of the project’s material poetics.

Canine (collaborative) archaeology in the making of Wastelands

‘Dogs are not just surrogates for theory […] Partners in the crime of human evolution, they are in the garden from the get-go, wily as Coyote’ writes Donna Haraway in her The Companion Species Manifesto (2003). I had already completed the Wastelands manuscript by the time I read Haraway’s manifesto but it resonates so perfectly with my dog Charlie’s active collaboration in the project, I nearly adopted it as an alternative epigraph for the collection.

I have already written above about the way Charlie and I worked together as ‘waste archaeologists’, excavating and uncovering waste materials together, but Charlie also led me into some important new ways of mapping and orientating myself within a place. Charlie wears a GPS tracker on his collar enabling me to capture his movements, even when I can’t see him. Charlie’s alternative ways of navigating and of responding to waste and wastelands inspired significant formal choices for the poetry itself.

In Wastelands, there is ‘a dog’ who wanders in and out of the text, and makes his own mark/s, and so I am not going to write too much more about his role here. His contribution to the book had a mysterious and more-than-human quality that resists description. I would invite you to experience in the poetry itself rather than trying to tell you about it here.

Here's a brief extract from the poem ‘Dog Pilgrim’ (of course the ‘dog’ in the poem is no more Charlie than the human is me, however the emergence of a human/more-than-human state of being as ‘dog pilgrim’ draws on some of our shared experiences):

Archival Practices in the making of Wastelands

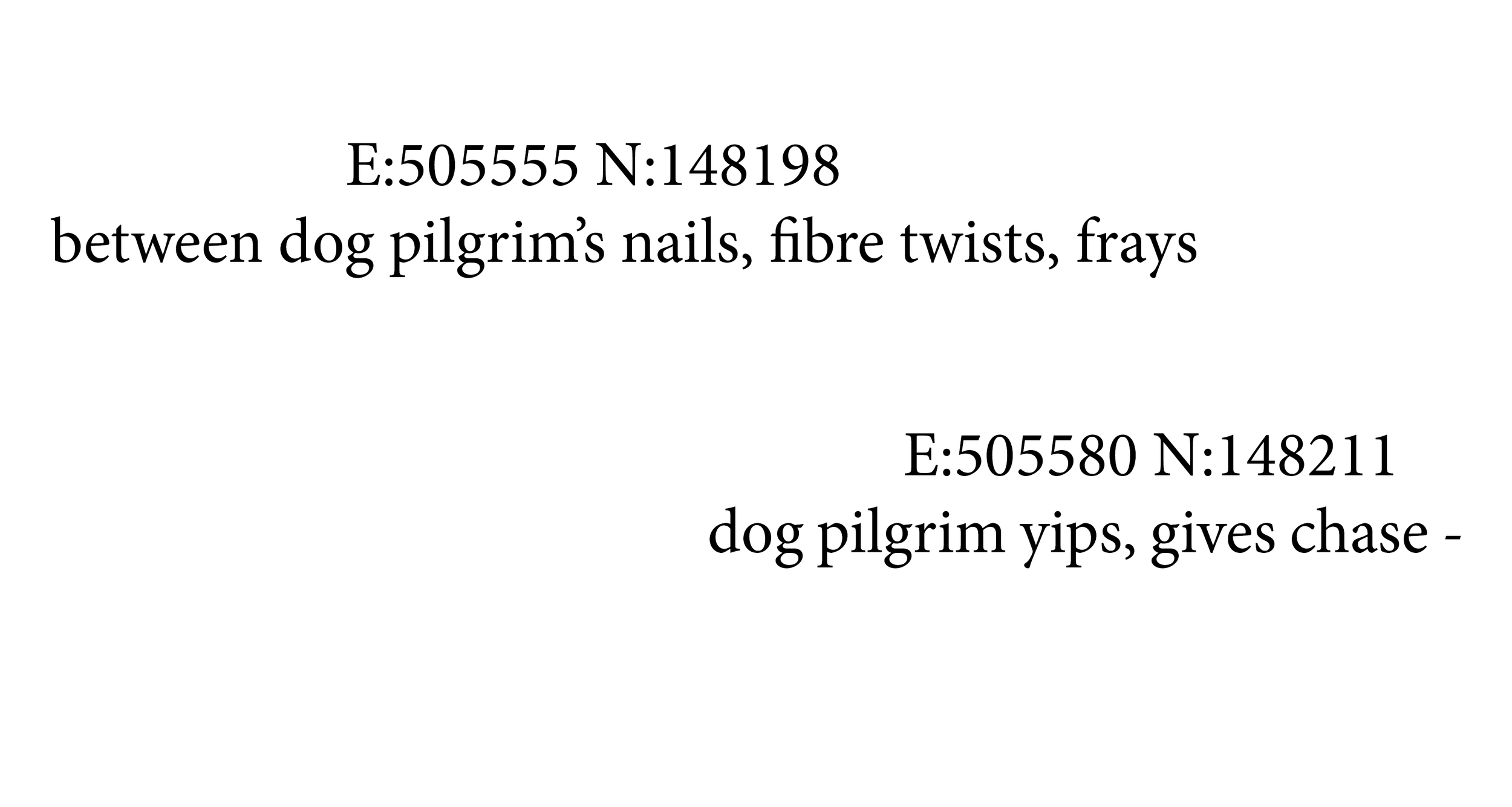

Illustration by William Hyde for Hilaire Belloc’s The Old Road

Wastelands is also a book for grieving what has been lost or damaged – a meditation on what has been laid waste externally but also on those inner wastelands of grief, despair and ethical disorientation. It asks how these wastelands of the inner world are related to those of the external world (and vice versa), and how might we navigate or map them (I have written about navigation as poetic process for the forthcoming issue of Long Poem Magazine). In this essay I have discussed in some detail the archaeological and material practices that were part of the project’s development but here I want to reflect on some of its quieter processes.

The book starts with the destruction of a way-marker, the fall of a great north-pointing tree, an environmental injury which happened on the same day as a personal bereavement so I was left lost and disorientated. I needed to find a way to navigate the wilderness of grief as well as to orientate myself within a problematic landscape, a landscape charged with what Robert Macfarlane has described as the ‘suppressed forces’ of ‘capital, oil, energy, violence, state power, surveillance’ which ‘pulse and flicker in the air […] waiting to erupt or to condense’ (Robert Macfarlane ‘The eeriness of the English Countryside’). I needed to make some kind of new internal structure to hold and orientate myself, as well as the poetry, within these frightening energies. As I’ve described, I used material poetic practices and rituals based on recovered waste materials, and I also explored textually what textile-based practices, such as knitting and repairing, might offer in terms of a looping, knotted, and patched poetic structure. But archival work and thinking about books always plays a significant – if quieter - part in the development of my work. From a literary point of view, Wastelands could perhaps be framed as a kind of ‘para-pastoral’, an uncanny, charged version of landscape art. The book engages with a waste landscape which resonates with Macfarlane’s account of ‘eerie’ landscapes (such as those of M.R. James) as ‘constituted by uncanny forces, part-buried suffering and contested ownerships’. But the starting point for the ‘wastelands’ motif, which came to dominate my thinking, is essentially from an older literary tradition of grail romances and quest narratives, the trope mentioned in my introduction in which the barrenness of wasteland is linked to a wound suffered by the king. Many of the significant texts which have engaged with the idea of a wasteland are alluded to within Wastelands: it remains a motif which feels extraordinarily relevant to our current times and yet is also problematic in its human-centredness. This became the kernel of the Wastelands project.

However, one of the most intriguing discoveries I made as I read more deeply was not obviously to do with the wastelands motif at all. I was intrigued and curious to discover the connection of not one but TWO famous ‘nonsense’ writers with the landscape of the book. Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) wrote ‘The Hunting of the Snark’ while walking the paths described in my poem ‘Stein’s Snark’ and Hilaire Belloc wrote his ‘pilgrim journal’ (The Old Road) about his attempt to walk and map what he helped to mythologise as a Pilgrim’s Way, walking directly along the edge of Weston Wood and what is now the landfill site explored in Wastelands.

Illustration by William Hyde. While Belloc’s text mythologises the idea of a unified Pilgrims’ Way, Hyde’s illustrations offer an alternative and uncannier vision of the landscape

Carroll’s nonsense often plays with redundancies in language which might be imagined as literary ‘waste’. In ‘The Hunting of the Snark’, Carroll dramatises a tension between the comical risks of inhabiting language as a system capable of generating its own (nonsensical or ‘waste’) meanings and the tragic risks of seeking a source of meaning and existence beyond it. (The Snark-Hunter who seeks a transcendental meaning by hunting the Snark high on a mountain-top, ends up simply ‘vanishing away’). It is this Carroll who appears as an unnamed ‘guide’ in ‘Stein’s Snark’.

But it was Belloc’s non-fiction text The Old Road which became most relevant to the later stages of my project’s development. Belloc’s text, implicated in some of the harmful, colonialist and totalising mythologies of place, has a problematic relationship with my own book. One of my developmental processes, discussed above, involved me gagging myself with a piece of recovered waste fabric in order to produce a distorted version of Belloc’s description of walking through Weston Wood.

Belloc’s version is as follows:

‘The Pilgrim’s Way […] makes for Albury Park by way of a wretched and sunken lane to the north of Weston Wood. We entered this neglected and marshy way. It was a place of close, dark, and various trees, full of a damp air, and gloomy with standing water in the ruts’ [The Old Road, p101]

Belloc’s language here draws on the motif of a wasteland. Whether cause or coincidence, the place he describes here as a barren and unhealthy waste is now actual waste: landfill. I responded by making a distorted ‘nonsensical’ version of this passage as it emerged from my gagged reading. It starts:

whe ennered hi neglected an mohorshy wae. e wash a wae o closh dark an bibbioush trees…

Hyde’s image illustrating this same passage

In the end I didn’t include these nonsense versions of Belloc in Wastelands but the physical, gagging activity emboldened me to approach other texts – some of them greatly revered, culturally significant, texts – to take them onto my own tongue and to breathe through them to explore their hollows and echoes, their waste edges and their still-evolving energies.

Archival research was also a vital part of the book’s development. I have written above about the ‘rescue archaeology’ that took place just ahead of the destruction of the historical Weston Wood site by extraction and landfill. I was particularly keen to access the archive of Joan Harding, lead archaeologist on the site and significantly, as I have discussed above, a retired librarian.

Detail from one of the site plans for the rescue excavations

I was able to access boxes containing many of her letters, diaries, and site maps but there was one box I was particularly keen to explore: according to the index this was the box which contained the original paper bags and old library index cards which she had used to store and label her finds. Despite the librarian’s best efforts, the box could not be located. Ironically, for a project which explores questions about what has been lost, destroyed, or thrown away, a key part of the archive had vanished.

Conclusion

Charlie, my canine partner in crime

I want to finish by reflecting on how waste doesn’t take place in a vacuum. The way we think – or don’t think – about waste is entangled with our human-centred mythologies of place and things, mythologies which distribute or erase value across the landscape, and across the materials we encounter. How we navigate our internal landscapes of loss and mortality is implicated in these mythologies, in the way certain materials become charged with our feelings about them as ‘overwhelming’ (too much meaning) or ‘left-over’, surplus to our requirements (not enough meaning), and in our narratives of ‘throwing away’ or ‘burying’ stuff in places we have designated as ‘empty’, ‘void’ (narratives of ‘emptiness’ which have of course been used to justify colonial expansion). And so Wastelands is concerned with these mythologies of navigation, orientation and place-making, as well as with the laying waste of places, internal and external, and the ‘wildness’ of waste itself.

But to say more about this would be to trespass on the realm of the poetry itself and so I will say no more here and leave it up to each reader to explore and navigate the book. I will leave the final word to Charlie, and he’s not telling!

Susie Campbell’s Wastelands was published by Guillemot Press in 2025 and is available here.