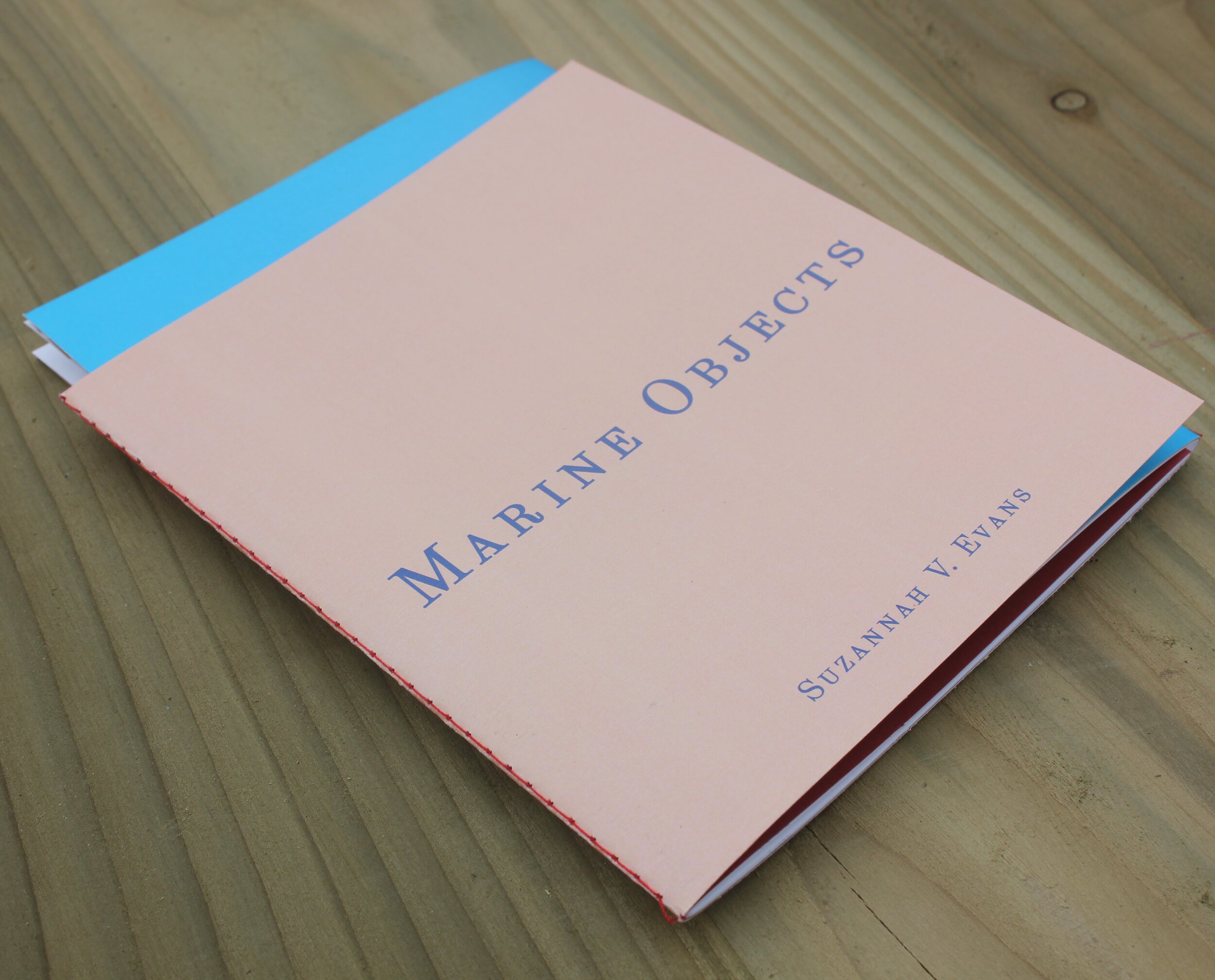

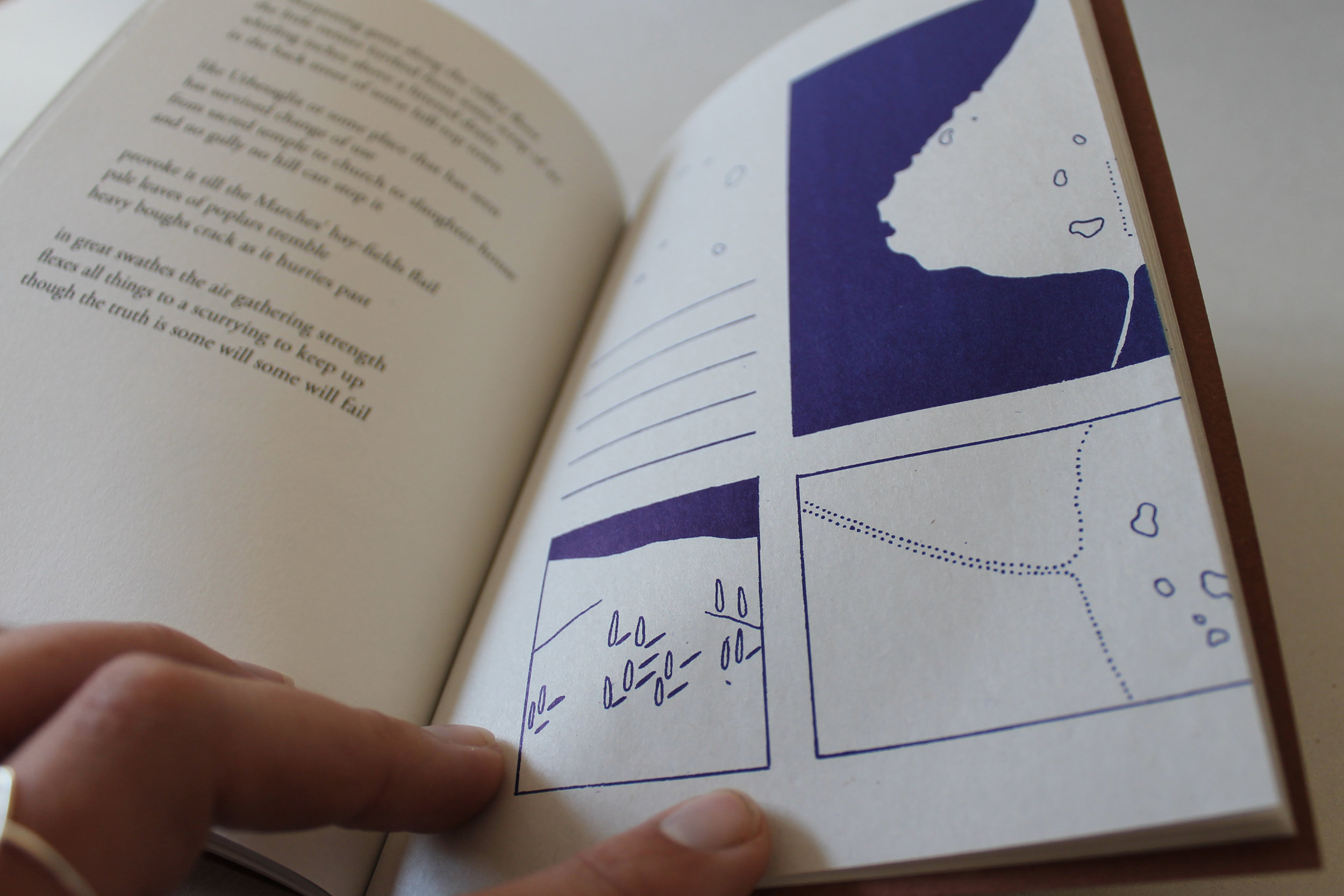

In April 2020 we published Suzannah V Evans’s debut double pamphlet Marine Objects / Some Language, which was illustrated and designed by Chloe Bonfield. We had been looking for the right project to approach Chloe with for some time and Suzannah’s text seemed (and proved) perfect. In this feature, Chloe gives us an insight into her creative practice and process, reflecting on language, emblemata and the relationship between text and image in her work.

On being presented with Suzannah V. Evans’s Marine Objects and Some Language, I immediately engaged with them as a pair, and simultaneously as distinct objects in and of themselves. I was drawn to the colours, to terracotta, and to a feeling that the two pieces were lightly holding each other — light pages with stiff tension.

The first reading evoked impressions from my own lived experiences. Before moving back to the city I had been working in care in Falmouth and somehow saw elements of this in Some Language. In a similar way to how I now feel the distance between here (London) and there (by the coast) I noted the distance between the voice of someone living in a place and experiencing tourists in Some Language. The feeling of watching someone experiencing something that you know so well. It seems to be more about a communication gap of some type, and for me this gap or hole links to desire. In Marine Objects I had the vague notion of ekphrasis but made a decision not to research this further so I could carry out my work.

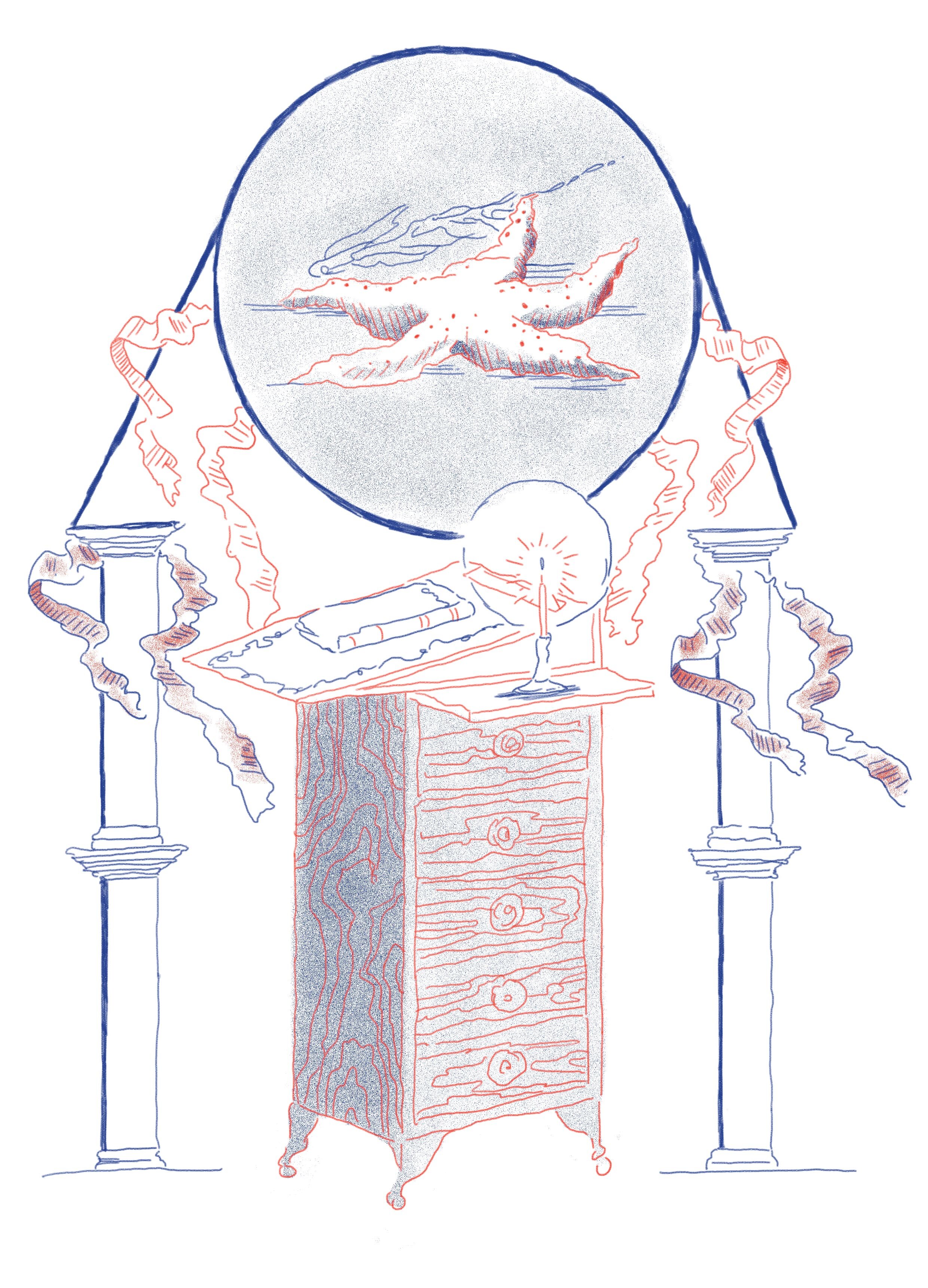

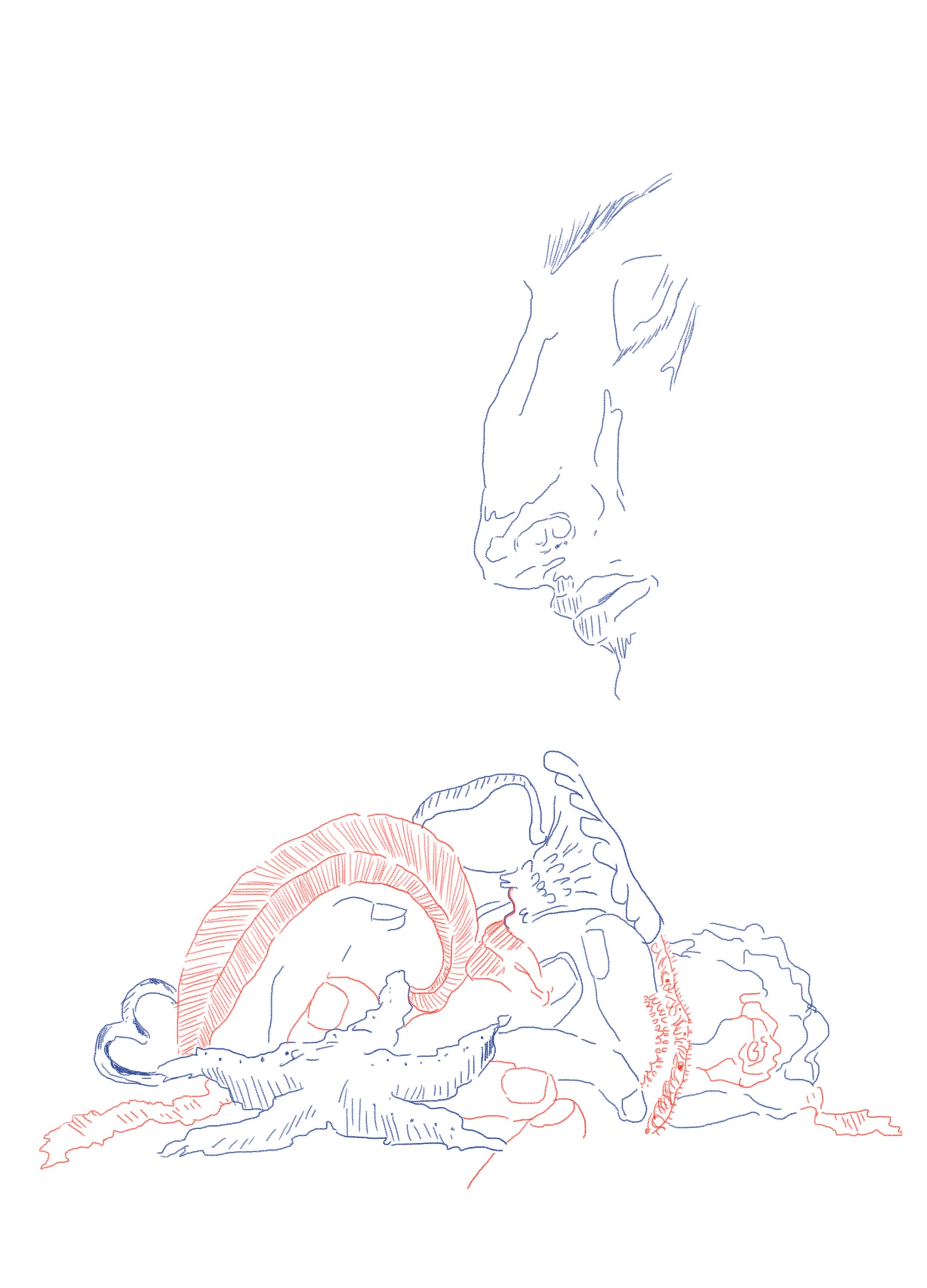

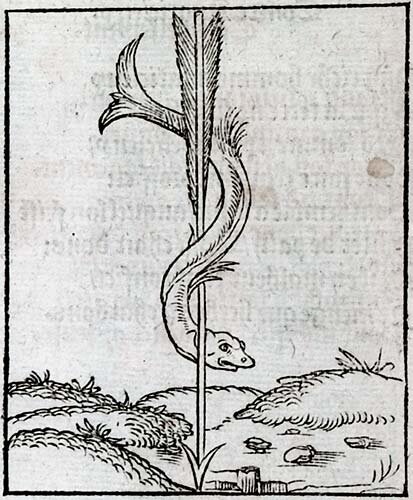

I wanted to approach illustrating the pamphlets using a method that I have recently come to through a mix of research and making, at the centre of which is the Emblemata of Alciato. The Emblemata as a form began in the 1500's and ended somewhere around the Victorian era. John Manning writes about it in his book The Emblem, saying that ‘[t]hey represent not so much a palimpsest, but the growth rings of a poet’s mind...’

I am particularity interested in how the image and text forms of the Emblem, whilst made with some form of artistry, are systematic in their method of production, and how this links to the creation of identity, language and culture. New images are informed by words, and those images live on to describe and transform the identity of an individual or a concept or even a society. Emblems are ‘veiled utterances’ where meaning is generated by dislocation. ‘The familiar, everyday or commonplace’, Manning says, ‘is changed by virtue of being placed in another context: it has become the bearer of unexpected meaning, a metonym for a previously hidden reality’.

‘Maturandum’, (By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Archives & Special Collections.)

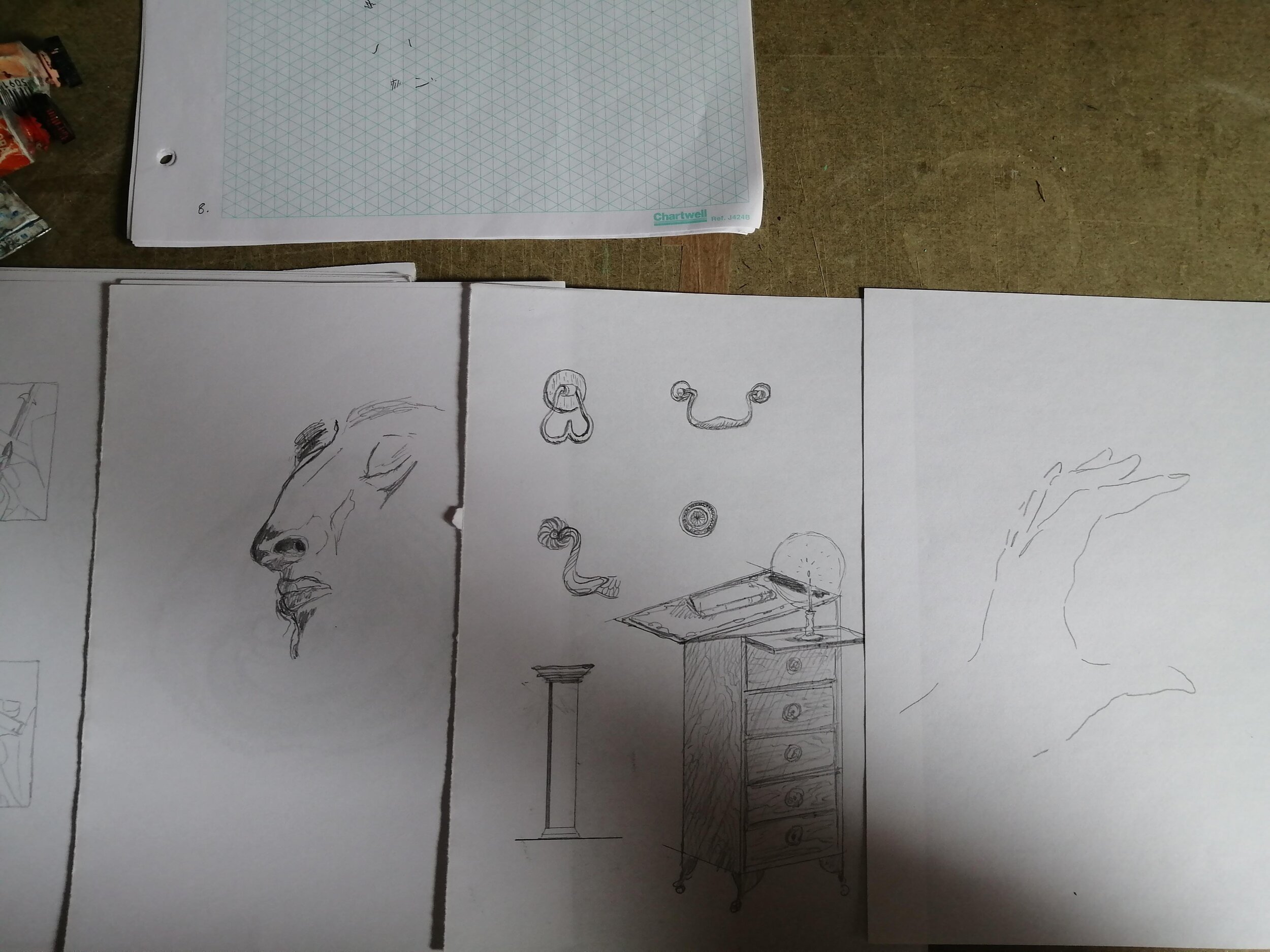

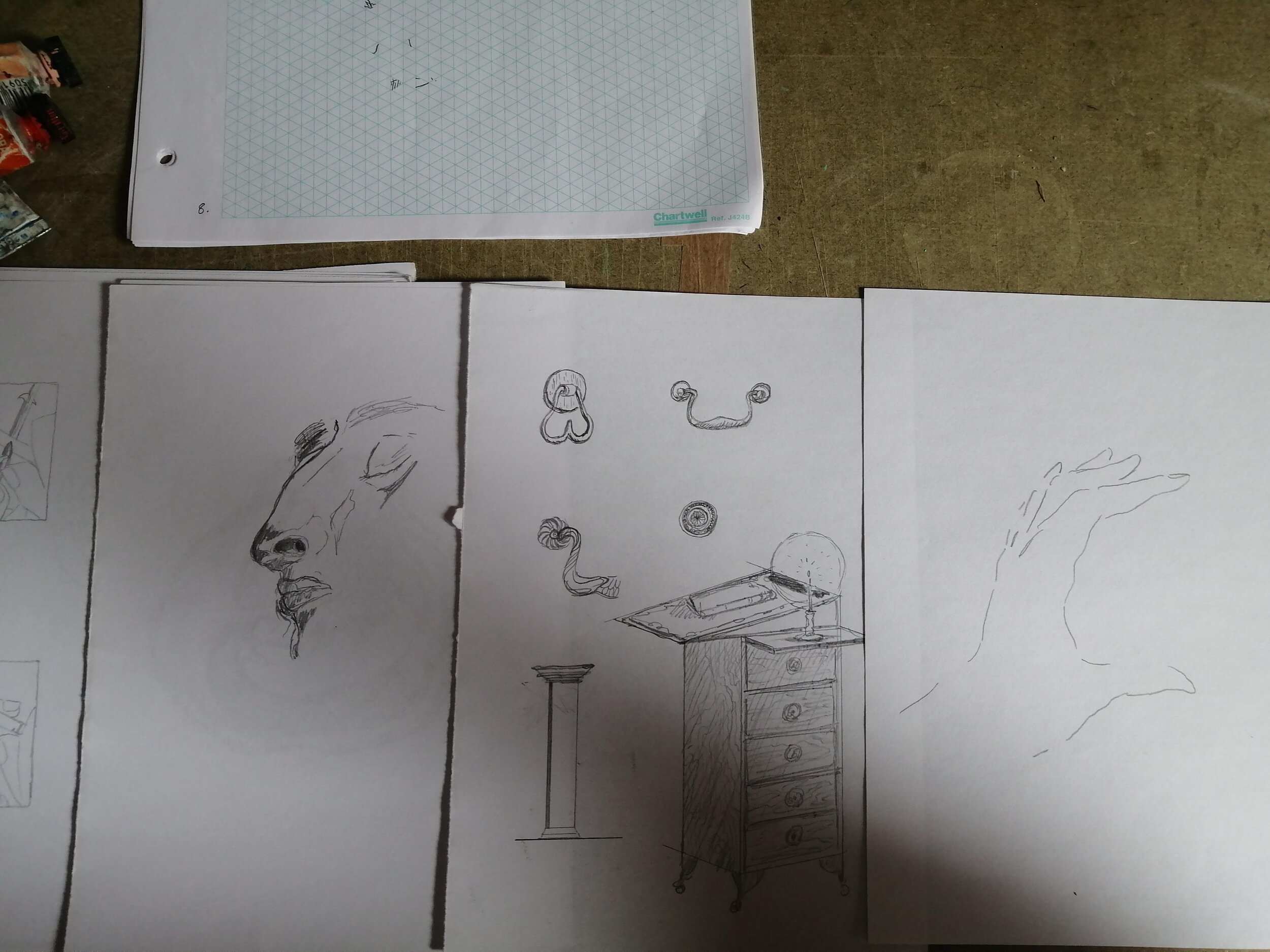

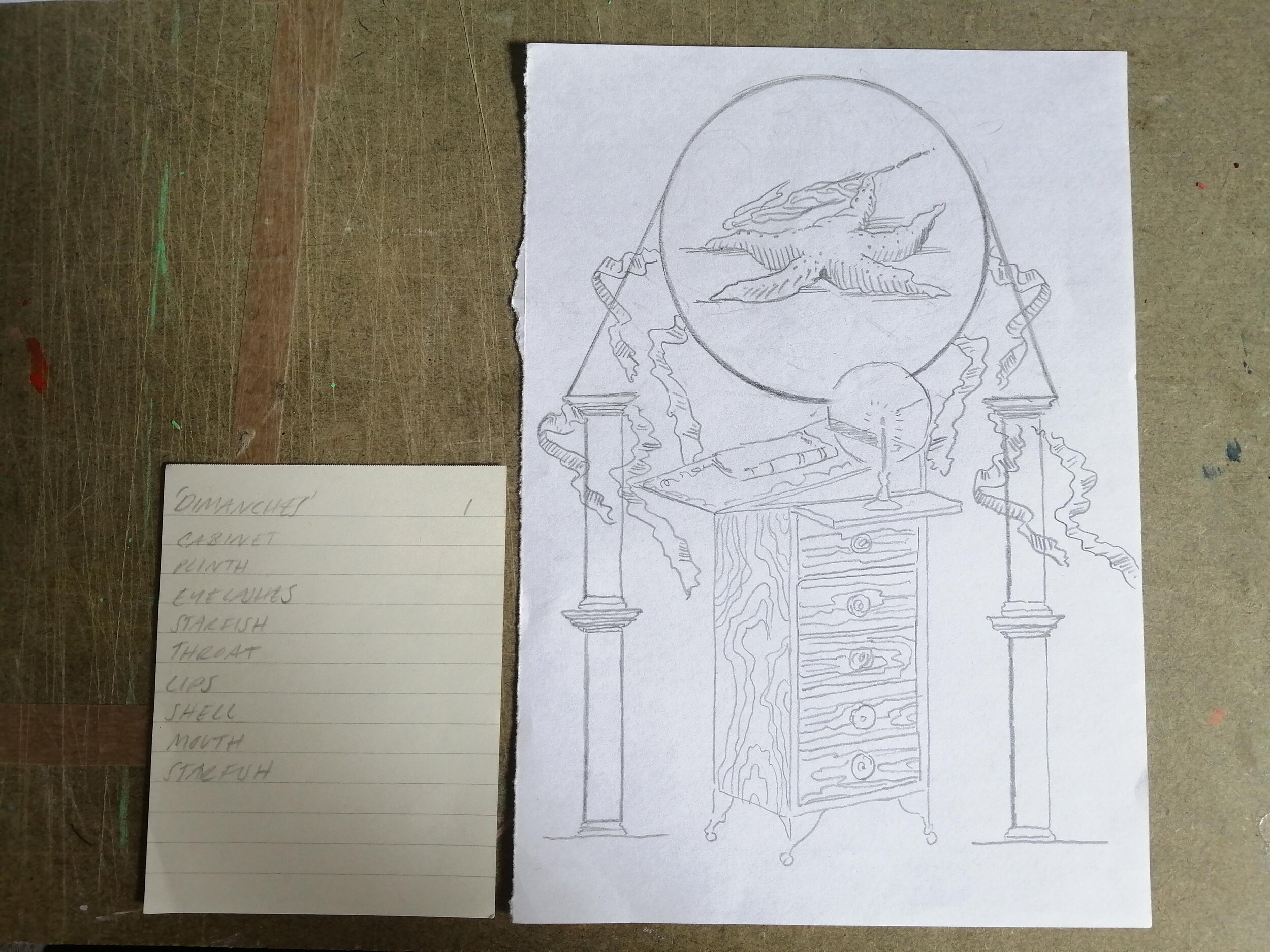

With this in mind I started to make the images for Suzannah's poems. From studying the way the wood block illustrations of the Emblemata were made, I made an inventory of the poems of Marine Objects, selecting words carefully and intuitively. It was a case of looking for those words that highlighted the objectivity of the poems, despite those objects gaining subjectivity within the poem’s structure. The way Suzannah uses language – deftly, with wit and unbelievable creative intelligence — created such an exciting space to work within. After taking inventory of these words I then used my own reference library of books. I like to think about these books from the viewpoint of taxonomy and classification — from Foucault's ideas in The Order of Things, or from Borges' essay 'The Analytical Language of John Wilkins', where the writer points to a list of arbitrary classifications that are shown to be absurd.

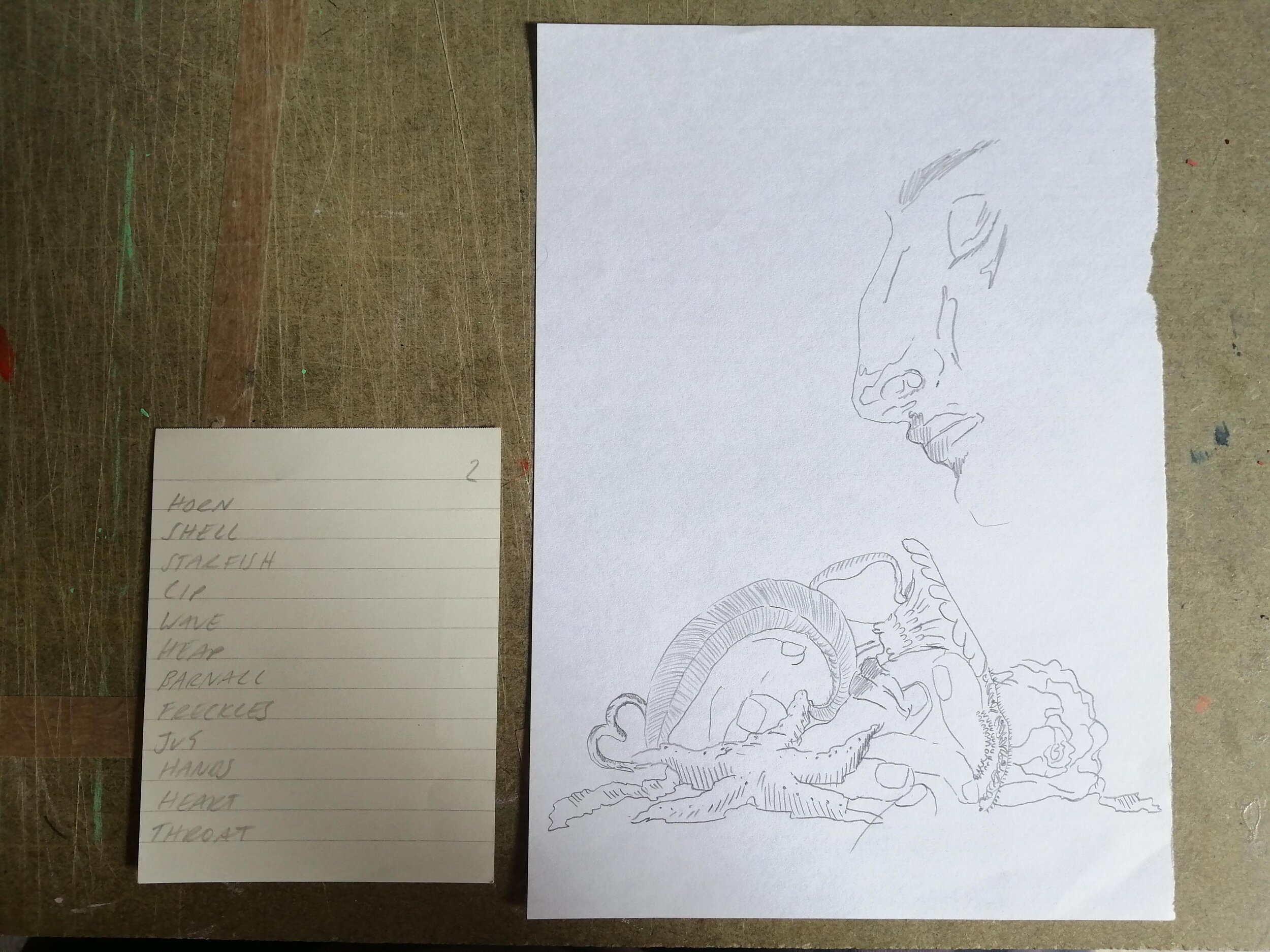

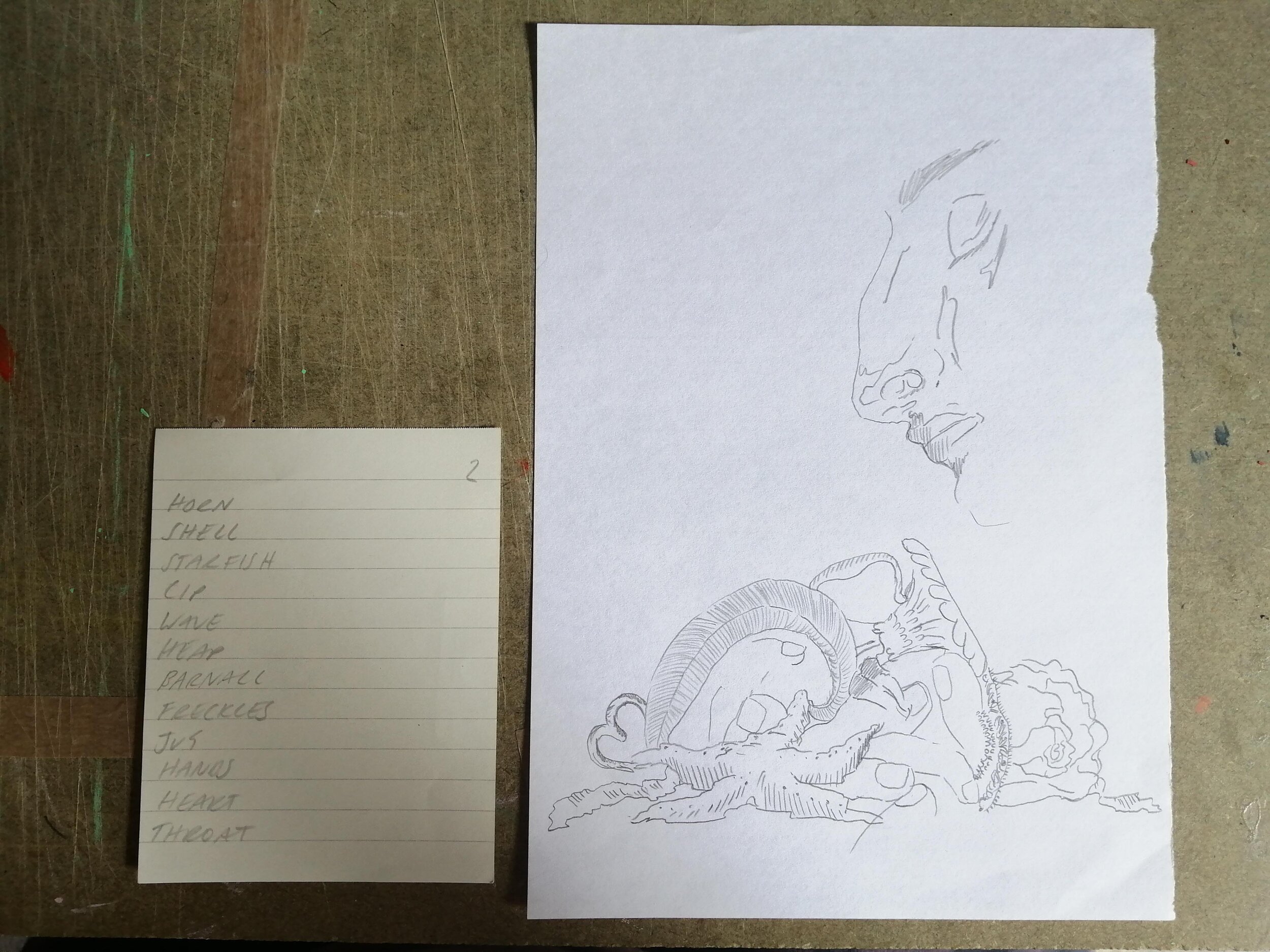

Engaging more particularly with the content of Suzannah's writing made me reach to the discourse of Through Vegetal Being, in which Luce Irigaray converses with Michael Marder through philosophical letter writing. Irigaray talks about naming things, about the meaning of this versus the physical embodied reality of experiencing the elements. She writes that ‘[m]ost of the time, we have lost the perception of the difference between meeting living beings and meeting things, be they material or spiritual, that we made’. When we talk about the Sun, do we see its face? This calls to mind the two lines from Suzannah's 'Starfish Balancing at Your Throat':

A horn, a shell, a terracotta, a yes, a lip, a burnished,

a thinking, a drowning, a crying, a barnacle, a wave, a heap.

Irigaray later writes how ‘[w]e ought to almost gesture in an inverse way, that is, momentarily consider ourselves objectively in order to decide how to pursue our journey’.

I used reference books to collage, chop and paste, drawing elements for each of the words I had in my inventory. When the wood block carver made their work for the poems of the Emblemata, they would work in a somewhat similar way. Some of them being illiterate, only an impression of the text might be passed on, resulting in a myriad of composites that built image cultures for hundreds of years.

Once I had covered the words in the inventory I used a light box to bring these composite parts together. This is where a balance of intuition and contemplation entered in earnest.

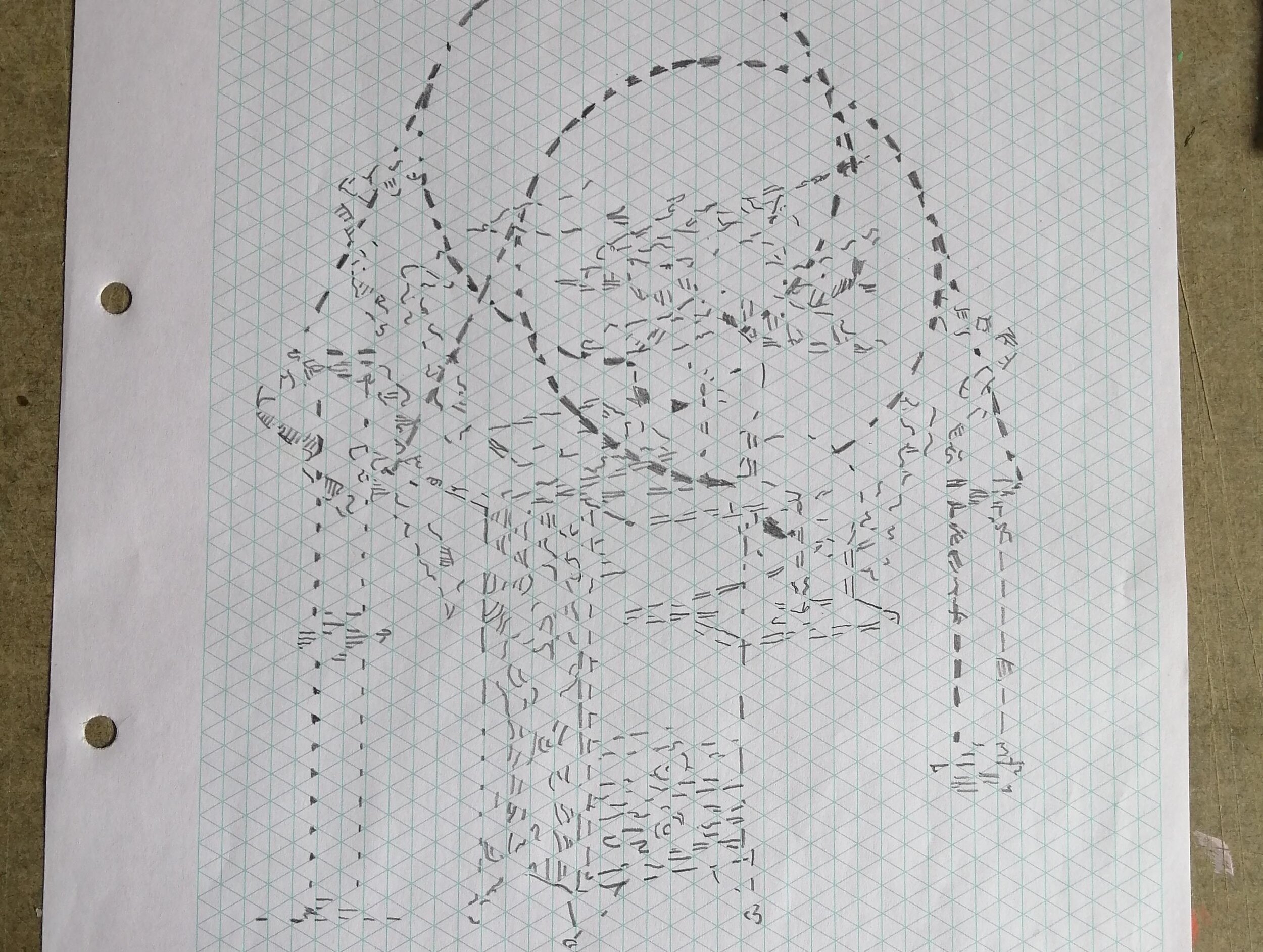

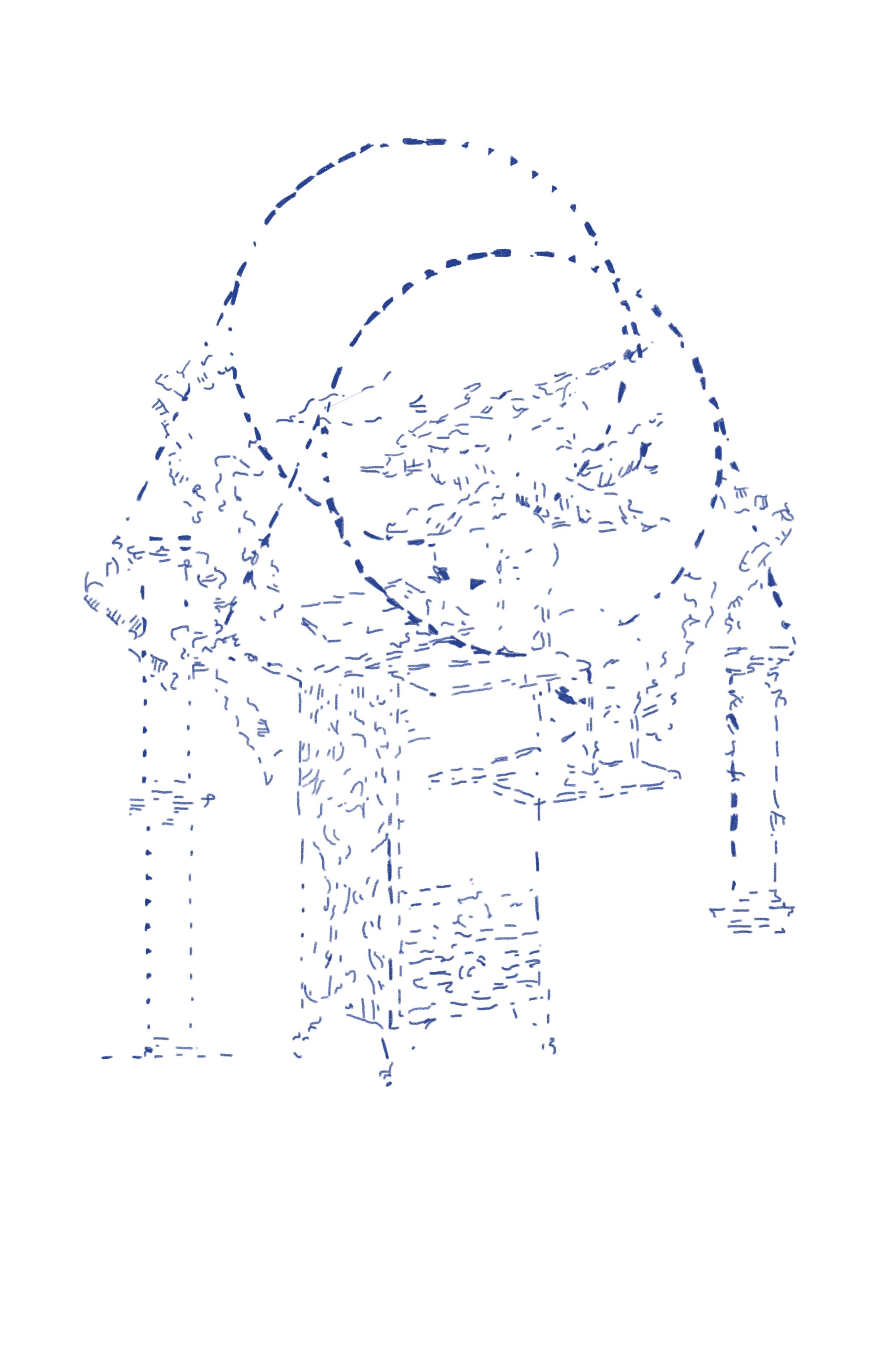

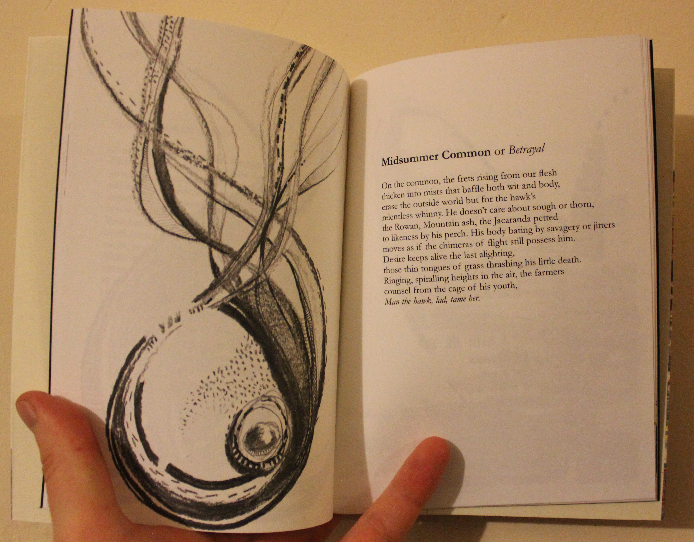

The Emblemata were travellers. The same images were reused, and the same emblems worked their way through volumes and centuries. Whilst thinking of the classification and deconstruction of categories combined with a desire to push the emblematic process further I began to rework illustrations in grid format, the grids either hand drawn or derived from an arbitrary source like a stationary shop. I feel the nature of Some Language lends itself to a fractal and mobile version of words, and suited itself to this method. Working through the illustrations made for Marine Objects, I re-drew them through grids of graph paper, making turns of ninety and 180 degrees of the drawings, imagining them as travellers to be paired seemingly randomly with Some Language.

I still at this point had not paired the poems with the illustrations. I find a thrill in doing this, in leaving it until I need to make the final layout. At this point in the process I am also thinking about paper, layout and space, as well as a container. That is, how the books will hold or frame the text and image conceptually.

Whilst these thoughts were building, I worked up the pencil drawings digitally. I have several reasons for doing this. Firstly, I have an interest in the digitisation of images and how they can connect with identity, both cultural and personal, and with linguistics. Once digitised how the images translate on the screen, especially when there is also a print version, is fascinating. I work as a print maker, and I use this method to ready my images for print. But further to this there is the physical action of using a tablet to trace over the lines drawn in pencil. Those broader sweeping lines were erased and duplicated, becoming obliterated by one strange thin line made by my hand, attempting to outline the idea that has been made, which in itself is a kind of ekphrasis. The lines become wiggly, odd, distorted further yet still familiar. The colours are simple, easy to replicate in print in concise ways. Then the grids disappear from the images I have drawn, taking away the frame that shows how they are made and what they mean.

Returning to the container of the pamphlets, which ran alongside this process, the thought of the books holding one another persisted. I started to see the pages interlocking in some way. Working with papers from stationary shops, echoing the grids and graph paper process, I found a pair of exercise books that became a blueprint for the pamphlets’ physical structure. They were both gridded and had singer sewn spines. The covers were stiff and the inner paper stock very thin and delicate. I tried to comb these two together putting their pages one within the other and found they held each other in a tension a bit like a Chinese finger trap. If you pull too hard they won’t let go, but by carefully leafing through the two books they become separated again.

As a layout started to form it felt like this could go a little further, and that the layout needed some space within it. Something to suggest the two were reaching out to one another. Here the idea of fold out pages emerged. The singer sewn spines and stiffer covers would hold them flat, and the end papers would echo the lips, shells and crustaceans, as well as mustard trousers.

Once production had begun I felt ready to look further into the ekphrastic nature of Marine Objects. Reading now inside the back of the book Suzannah writes:

'Marine Objects is based on Eilieen Agar's sculpture ‘Marine Object ‘(1939). In A Look at My Life (London 1988) Agar describes collage as ' a form of inspired correction, a displacement of the banal by the fertile intervention of chance or coincidence'. Words I borrow for the opening of 'Balanced and Barnacled'.

In her introduction to poems in The Modernist Suzannah says that some of the poems of Marine Objects / Some Language were written in response to an exhibition in Cambridge inspired by the writing of Virgina Woolf. I saw a similar show at Tate St Ives. It added a weight to the iterative feel of these poems, their relationships with existing art works and literature, and the potential to continue the iteration through publication.

Discovering the links between Suzannah’s influences and the emblematic process that I followed was very exciting. It echoed just the kind of poetic contemplation offered by those emblems and by the text and image relationship. I am glad to have followed this playful and systematic form of collage to illustrate these books. I particularly enjoyed the revelation of Agar’s sculptural work that began Marine Objects, which brought me closer to the idea that the bond between the text and image can have a material, or at least, ‘object’ quality. The transition of this into cerebral thought in Some language completed the conversation.

Chloe Bonfield is an illustrator, writer and researcher working in London and the South West. You can visit her website here. And you can buy the double-pamphlet Marine Objects / Some Language here.

References:

Borges, Jorge Luis. The Analytical Language of John Wilkins. 1952.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things, An Archeology of Human Sciences. 1966.

Irigaray, Luce. Through Vegetal Being, Two Philosophical Perspectives. 2016.

Manning, John. The Emblem. 2002.

The Modernist Review : https://modernistreviewcouk.wordpress.com/2018/12/18/some-ekphrastic-poems-on-eileen-agars-marine-object%EF%BB%BF/