Cat Chong

‘Poetry permits a speaking from the margins’ has seemed a commonly accepted assertion in my life over the last few years. Typically, this referred to the margins of race, gender, class, and sexuality practicing interventions into language which enacted a speaking back, a speaking out of places of erasure. I recently read that ‘disability is the last margin to be addressed’ (Scior and Werner, 2016) and while I know this idea isn’t new I realise that while I was studying I never encountered a contemporary poetics that engaged with neurodiversity or disability.

As I was trying to counter this lack of representation within academia and poetry, I started attending events in London which spoke to my subjectivity as a poet and as a disabled individual. These were often organised and run by people like me, and I attended because I felt compelled to validate the belief that I am not alone. I wanted to be with others like me and to commune together about embodied difference in a way that didn’t feel like I had to confess anything. When I did eventually find these places, they felt like home. I felt like I belonged there. Even without a diagnosis I was able to engage with my identity as a disabled poet in a way which felt sincere. I was simply being, and that was alright.

Creating space for women interested in and sensitive to neurodiversity is the aim of The Poetic Spectrum workshop hosted by Jen Hadfield, an award winning poet who herself is neurodiverse. The workshop recognises women without a diagnosis, who identify Autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) traits in their personality, acknowledging how ASD presents differently in women than in men (and welcomes any woman who would describe herself as neurodiverse in any other way). I wanted to ask her what it’s like occupying multiple marginalities as a poet, to navigate neurodiversity and gender in a way that feels generative, to discuss some of the ways in which neurodiversity and disability overlap and intersect in poetry. I was curious about what it was like to organise safe, communal spaces and how this affected her experience of poetics and the role of the poet.

Jen Hadfield

So I notice, first of all, that you choose to describe yourself as ‘disabled’ and that you mention ‘neurodivergent poets’ – these two things aren’t necessarily connected of course.

Cat

But there are areas of commonality. As someone with a chronic illness, my disability is invisible. There’s an assumption that because I look healthy then I am healthy. This assumption is made by friends, family, and even doctors. It’s one of the reasons it’s so hard to get a diagnosis. As a result, at times I spend a great deal of time compensating for being ill.

In a seminar with Broc Rossell, he said that ‘poetry is a sensitivity to language’, and I think the same can be said of neurodiversity and disability: neurodiversity and disability can create a sensitivity to language – connecting communication, poetics, and atypical phenomenologies. To me, explaining symptoms to doctors, lecturers, and those around me involves selecting the right words in the right order, and is to be taken seriously. Having spent years without a diagnosis, narrating my own experience without a medical way to signal what it is that makes my body different, is difficult. For me, it’s hard to tell the truth when it doesn’t have a name for anyone to recognise. It took a long time for me to identify myself as disabled. The word was covered in projections of shame, most of which came from my family and those around me.

Jen

This has been quite hard for me to navigate personally and professionally (I feel quite vulnerable explaining why I describe myself as neurodiverse) so I’ve spent quite a bit of time lately unpicking why I feel like that. My way of talking about it now is this: I definitely recognise an interesting array of neurodiverse traits within myself that are often associated with Aspergers. I don’t have a diagnosis, but almost certainly should do, for reasons I won’t go into too deeply here, mostly because to do so gets too personal. I think the reason I don’t is that women present very differently and the clinical approach hasn’t quite caught up yet – something that’s been discussed a lot on Radio 4 in the last couple years. Some of these traits are difficult/uncomfortable to live with and have given me some grief over the years, although I’m relatively comfortable with them now. Others feel like genuine boons. Women work harder than men, we think, to mask such traits as don’t conform to social and cultural mores, and sometimes you don’t know you’re doing it. Have been doing it all your life. That’s hard work, and sometimes it goes wrong, and I think there is a kind of violence you can do to yourself by denying your own needs in this way. On the other hand, sometimes it means that you’re treating other people with a lot more conscious care and responsibility. Either we learn intellectually (if we choose to) how to empathise and ask questions and express our own feelings and thoughts (I shouldn’t say we, here, there’s too much variation to do that) where others do so innately, or we do it just as innately, but later … or others learn how to do it as much as we do, but earlier in life – I don’t know. Anyway, I think our feeling for folk – for example – and our care of others is no less authentic and valuable for developing in this way.

At any rate. I think that the way I want to tell my own story, and the way that feels true to me, is that rather than me being a neurodiverse person as opposed to a neurotypical person, is that maybe everyone by definition of being a person is neurodiverse in some way or another. How does that sit with you as an idea? What it gives me is dignity, of course; and it refuses the collection of paradigms that say ‘these people are more normal than these people over here’. What the massive underdiagnosis of Aspie women for example has signalled to me is that there is such a huge hidden population of people that would probably call themselves neurodiverse if they didn’t feel that was a stigmatising thing, as to probably represent a really significant chunk of the population. But then there are all these other manifestations of diversity too, so why do we insist on calling ANYONE normal? Everyone’s got something going on, right?

Cat

We all do have something going on now, with lockdowns imposed in a majority of countries, the covid-19 crisis has highlighted our reliance on community, connection, and our ability to change the way we conceive of work, especially work from home. It’s been incredible to see the speed at which the world has become more accessible now that working from home has become an everyday reality for many people. Online poetry readings have proliferated massively and the term ‘Zoom’ has just about entered the common lexicon. It does have its benefits: if a discussion feels too loud I can simply turn the volume down; only one person talks at a time; I can do poetry readings in a shirt and the comfiest trousers that no one will see; and I get to do everything from the safe space of my bedroom with the ‘End Call’ button always in front of me.

When I was doing my BA, I was told that to be involved in poetry in London meant that I had to ‘be in the room in order to be counted’. At first this frightened me because of the huge amount of energy I knew it would take me to simply be in a crowded place with so many people, but after a while I slowly started to get used to it. By the end of my MA I could attend poetry events without getting too overwhelmed. This took some practice, though it always meant spending the next day in bed utterly exhausted. So much of poetry before the lockdown felt as though it was predicated on the spaces in which it communally took place, according to who was in the room, who was there, who was able to be counted. This has changed since the lockdown and I retain the small hope that this broadening of accessibility won’t evaporate when the lockdowns lift.

Jen

So, I am very sensitive to sounds, sometimes, especially when I’m tired. Busy places tire me out and make me a bit panicky after a while, and I find it hard to think straight in those places. NOT UNUSUAL TRAITS I don’t think, even for people who wouldn’t call themselves Aspies. I find it quite hard to talk sometimes (proper tongue-tiedness) but for others it’s very easy and I can be very articulate on subjects I like talking about, if I’m relaxed with the folk I’m with. That’s about the sum of it for me, except to say that that sensitivity to sounds, smells and colours and textures can be a really delicious thing under the right conditions.

Hm, where am I going with this? Oh, the workshops. So, I wanted, yes, to create an atmosphere of inclusion and as much calm as possible. One workshop was at Glasgow Women’s Library, and they invested a lot of time in getting this right with me. We had a nice spacious quiet private room and I made sure that people knew if they wanted to pop out or leave at any moment that was absolutely fine. I took care to talk only about my own experience and that of my sister where she had ok’d that, and to not presume to know anyone else’s experience. I would say that everyone in the group willingly shared traits that they themselves defined as neurodiverse, not that they had to do that. I wanted the group to be open to women who were curious about neurodiversity as well as those who would describe themselves as neurodiverse. We all gave each other time to talk as much as we needed, and we didn’t make anyone speak before they were ready. And the focus of the writing exercises, as I remember, was on language – was on writing as we speak, as closely as possible – so celebrating the diversity of our voices, and harnessing writing’s power to get across what we most need to articulate, even when that’s difficult. It was a wonderful experience for me because I felt like everyone felt comfortable with who they were in that room and enjoyed each other. And that we valued each other’s strengths and superpowers. Glasgow’s Women’s Library also said, not only were we oversubscribed, but that normally with free weekend workshops they normally see a no-show rate of about a third. We had MORE people than were booked. They were really surprised, and I think that too points at the fact that there are a lot of people out there who have needed a different format/focus in writing workshops.

The other sessions were mostly a talk/reading kind of format, but I shared a few neurodiverse traits of my own and just asked folk to consider whether they recognised any of those traits in themselves, whether they called themselves neurodiverse or not. I was quite shocked by the number of people who came up afterwards and said they felt I was speaking very directly not only to their own experience but that of many of the people they knew. Of course, an arty crowd is sort of self-selected, often, and we’d maybe expect to see a lot of quite sensitive people there … but still, I was surprised, and it felt very positive. I did feel very nervous before some of these events. I took in feedback forms and the responses were various but mostly very warm and positive and appreciative; there were maybe just a few stupid comments like ‘lovely feminine reading’ !!!!! but everything about neurodiversity was very encouraging and actually gave me a lot more confidence to talk about this stuff. I will say that after a reading in St Andrews this week where I was quite nervous, I felt very keenly the need to develop a way of talking about this stuff that can be both professional and personal. When it feels too personal, it feels like I’m baring my soul in an unhelpfully confessional way and making myself vulnerable. When I get the balance right, I feel fine about myself and positive about my subject. I think that variability is coming from decades (or more) of stigma and misunderstanding about Aspie traits and neurodiversity though and I’m quite committed to challenging that. I feel like it SHOULD FEEL SAFE.

Cat

I’m curious what it means to speak out of difficulty. I want to think about this in relation to the poem ‘The Asterism’ in Byssus (2014) which is preceded by a quotation from Annie Dillard's A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek:

a mystery, and a waste of pain

The first line of the poem is addressed as if to an 'Inexplicable pain – / ... a thing like Sirius / or Aldebaran –'. I wonder how you navigate difficulty within the fragile structures that constitute the written and spoken word? Between ‘effortful’ and ‘proper tongue-tiedness’ and ‘sudden flu-encies' to say ‘what we most need to articulate, even when that’s difficult’?

Jen

I think I just try to be honest about them. After my reading at StAnza, a friend said she wondered how people could take on board what I was saying about struggling to speak when I was talking about it so fluently in poetry! The point is that writing a poem very practically helps you rehearse what you need to say. And say it as powerfully as possible. To score in breath when you know you will need breath. To take out clusters of sounds that are hard to say. And to self-hypnotise into a calm state where speaking is more possible. Also, I think if you can hypnotise yourself with a poem’s rhythm, you probably also hypnotise a willing audience! Then they too have the opportunity to process stuff … Perhaps …

Cat

I really appreciate this strategy for reading. I've only started to read my work publicly in the last year and I still find the prospect of pronouncing my work, out loud, quite daunting. The process of putting my body to and into a text was something I wasn’t sure I felt confident doing.

According to the National Autistic Society, ‘various studies, together with anecdotal evidence, suggest that the ratio of autistic males to females ranges from 2:1 to 16:1’. The most-up-to-date estimate is 3:1 which was found in a study by Professor Francesca Happé, the director of the Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Centre at King’s College London. Within the same study Happé and others believed the ratio could be potentially as low as 2:1 – ‘as diagnostic processes become better tailored to identifying autism in girls and women’ (Delvin, 2018).

To situate diagnosis within the realm of poetics – framing the process of diagnosis as a medical form of labelling and meaning making – spoke to the poem Love's Dog in your debut collection Nigh-No-Place (2008). The poem begins with a lucid declaration about the conflicting responses to this legibility within diagnostic identification. The poem begins with:

What I love about love is its diagnosis

What I hate about love is its prognosis

I've been thinking about this a lot; the love of a name while hating the predicted future projected by that name. Like loving a signifier and hating the signified, the poem seemed to suggest what they love about love is the sound, the word, the image of the diagnosis, whilst hating the rigid and concrete boundaries created by a prognosis’ parameters.

I think there’s a loving and hating involved in being ‘hidden’, in being invisible. I feel this a lot in relation to my own undiagnosed chronic illness but I’d never thought about it in relation to love before reading Love's Dog. I’d never thought about the invisibility inherent within an invisible disability in relation to love as an emotion, as sensation, as act, and affect. I realised that within the rigorous medicalisation of my body – in my attempts to understand what was happening to me, – that I’d internalised the loveless lexicon of medical science. I’d never thought about my body and disability as inhabiting a space of love. In reading your work, I spent a great deal of time considering the limitations of vocabularies and language itself in relation to experience. So far, I’ve found two ways to approach diagnosis as a naming; either diagnosis reduces an experience to the word or there is a failure to name.

In The Argonauts (2015) Maggie Nelson seems to describe the former when she quotes her partner Harry as saying: ‘Once we name something, you said, we can never see it the same way again. All that is unnameable falls away, gets lost, is murdered. You called this the cookie-cutter function of our minds. You said that you knew this not from shunning language but from immersion in it, on the screen, in conversation, onstage, on the page.’

Prudence Bussey-Chamberlain described the alternative, the inability to get a diagnosis viscerally as, “you are wordless expanse of affect and sensation without a name”. In my work, I've often tried to disrupt the sentence and the medical language of sickness to create a kind of rupture between the signifier and the signified in relation to chronic illness, to try and make space for my own identity as disabled without invoking the stigmas of shame and pity that are typically attached to disability. The influence of stigma seems to cause the same kind of alienation when recognising neurodiverse traits.

Jen

There is such a huge hidden population of people that would probably call themselves neurodiverse if they didn’t feel that was a stigmatising thing, as to probably represent a really significant chunk of the population

Cat

I think both neurodiversity and disability find an alliance through poetics, in the poem’s ability to intervene into the language of diagnosis, prognosis, and scientific discourse; it can be a space for staying with the possibility of failure in naming, in lacking a diagnosis, in struggling to speak out of difficulty.

Jen

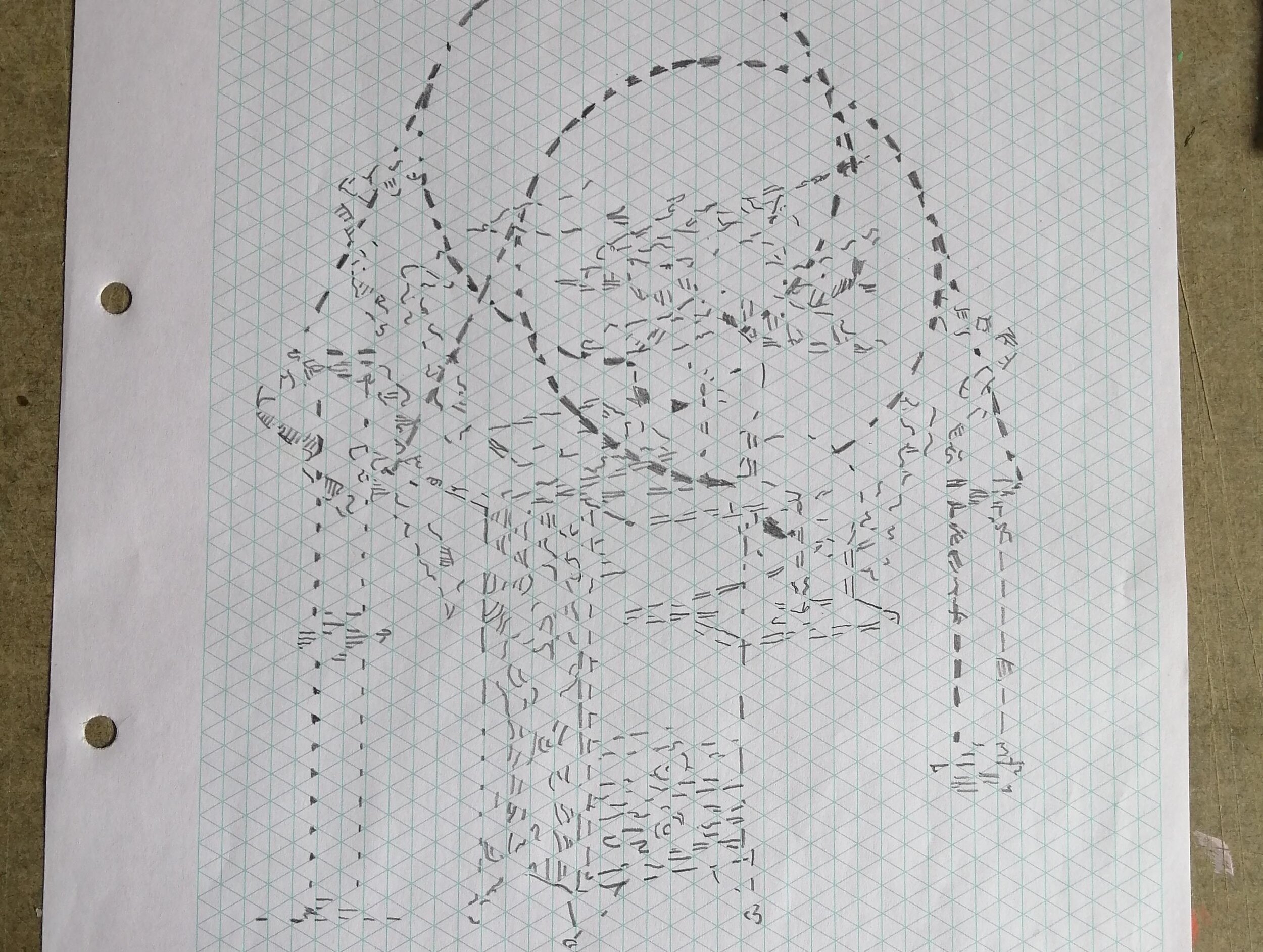

I think the apparent contradiction here maybe isn’t too much of a contradiction. Language/names are power right? And our way of owning our experience. I met a bunch of art students a couple years ago a lot of whom expressed being intimidated by the need to describe their own creative vision in WORDS in their critical essays/programme notes/biographies/theses … because they articulated themselves most comfortably in other media, but also because critical language felt like it excluded them (it can exclude writers too I think!) To learn to write critical language is empowering; however I really think it’s the critical language and the power associated with it (you pass or fail depending on whether you can learn to ‘speak’ this foreign language!) that is the problem. Making any kind of language like that your own; transforming it creatively; replacing it with a personal chosen language … is a positive, empowering act. I still hope we can culturally evolve to hear each other describe our own experience in different ways though, rather than relying on language we’ve ‘had done to us’… and maybe that is quite relevant for disability and diversity too. It’s just another cultural norm –– with its own cultural history –– the authority such language suggests it has is really quite subjective. Similarly –– where does my sensitivity to sound and movement make me atypical? Only in the context of post-industrial cities for example? That book “Quiet” is quite good for challenging the assumptions that ‘extrovert’ is ‘normal’ and from there on in I think you can play at dismantling all of those structures about what ‘normal’ is.

Cat

I read the poem ‘In Memoriam’ as a response to this difficulty in voicing our own subjective embodiment, starting with the quotation by Iain Crichton Smith which prefaces the poem:

No metaphors swarm

Around that fact, around that strangest thing,

that being that was and now no longer is.

To me, the quote is reframed within a context of an absent language never having been there to begin with, rather than a loss of Gaelic as a language specific to the geographic region. The poem seems to advocate for animal tongues, for sound, and sensation as an alternative place out of which communication can arise.

I

For it is not like a sea of nested gas

that you float upon

in your pedalo.

This unspeakable is not like

anything

a poem or riddle collies no particle

of it for us to fank

in mouths and minds.

II

Loving language is wide

and shallow: sooks, polches

and wistens it.

Already I can only noun

about its shores

and surfaces

nym the brinks of this squilly thing

where congregates stuff

that can be likened:

III

First we’ll need

to agree:

are we taking up the first language

or must we coin

a new one?

I found a similar sentiment in your essay ‘A Higher Language: What Iain Crichton Smith Couldn’t Say’ (2011) which meditates on ‘what language is, and what we lose when a language is lost’. How do you manage to negotiate the inadequacy of language and the loss of it within your process? Whether there can be an answer to 'are we taking up the first language / or must we coin / a new one' in order to find voice?

Jen

I suppose – I hope this doesn’t sound callous – that finding a language is always a positive gesture towards any difficulty, for me; whether or not the language can adequately convey the experience doesn’t trouble me too too much – if it can wake us up to experiencing something universal or familiar or personal and specific in a way that CHANGES SOMETHING for the writer/reader I think we’re on the right track. And when it’s working, I feel that as a palpable relief and release from stigma/difficulty. It increases my sense of self-worth too. But yes, I think it is always worth ‘coining a new one’. I also think it’s worth trying to be very straight forward and simple and clear sometimes too. Maybe the act of making something beautiful (in image/in recognition/in surprise/in music) in response to something difficult is like a demand on the reader to say, not only do I claim this experience as my own, but look, it’s WORTH something. We are definitely alive. We have a life. And we will celebrate it. To write about something also allows us and our readers to turn it around in their hands and look at it from different angles. It makes frightening, immense, overwhelming experience something we have a chance of tackling at our own scale. We can say it, read it, close the book, open it when we’re ready.

Cat Chong is a poet, transcultural twister child, and a proud queer crip. They're a graduate of the Poetic Practice MA at Royal Holloway and current PhD student at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore where their research focuses on the intersections between gender and medicine to investigate contemporary female experiences of healthcare. Their interests include ecology, feminism, gender, health, contemporary poetics, medical humanities, and disability studies.

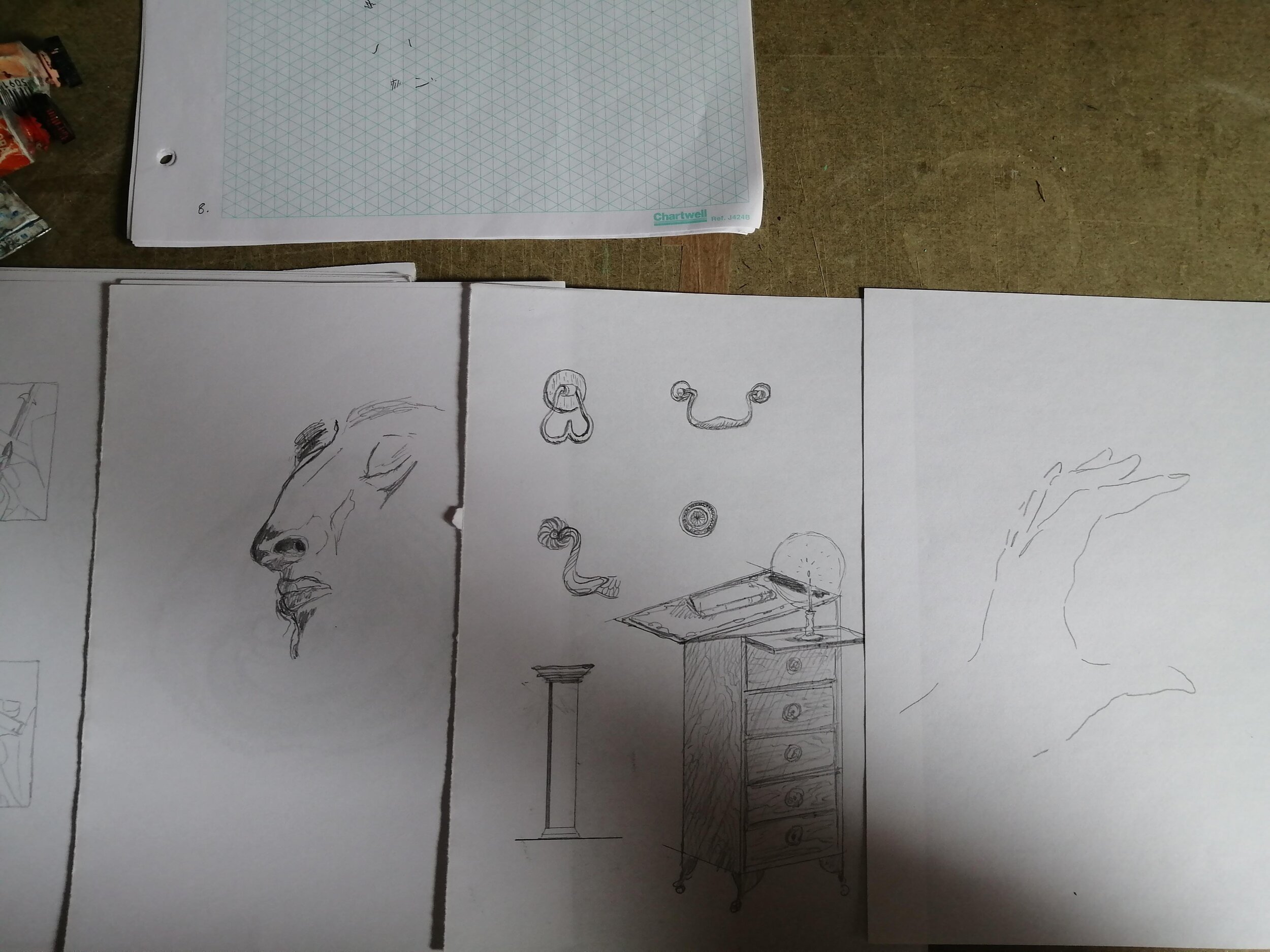

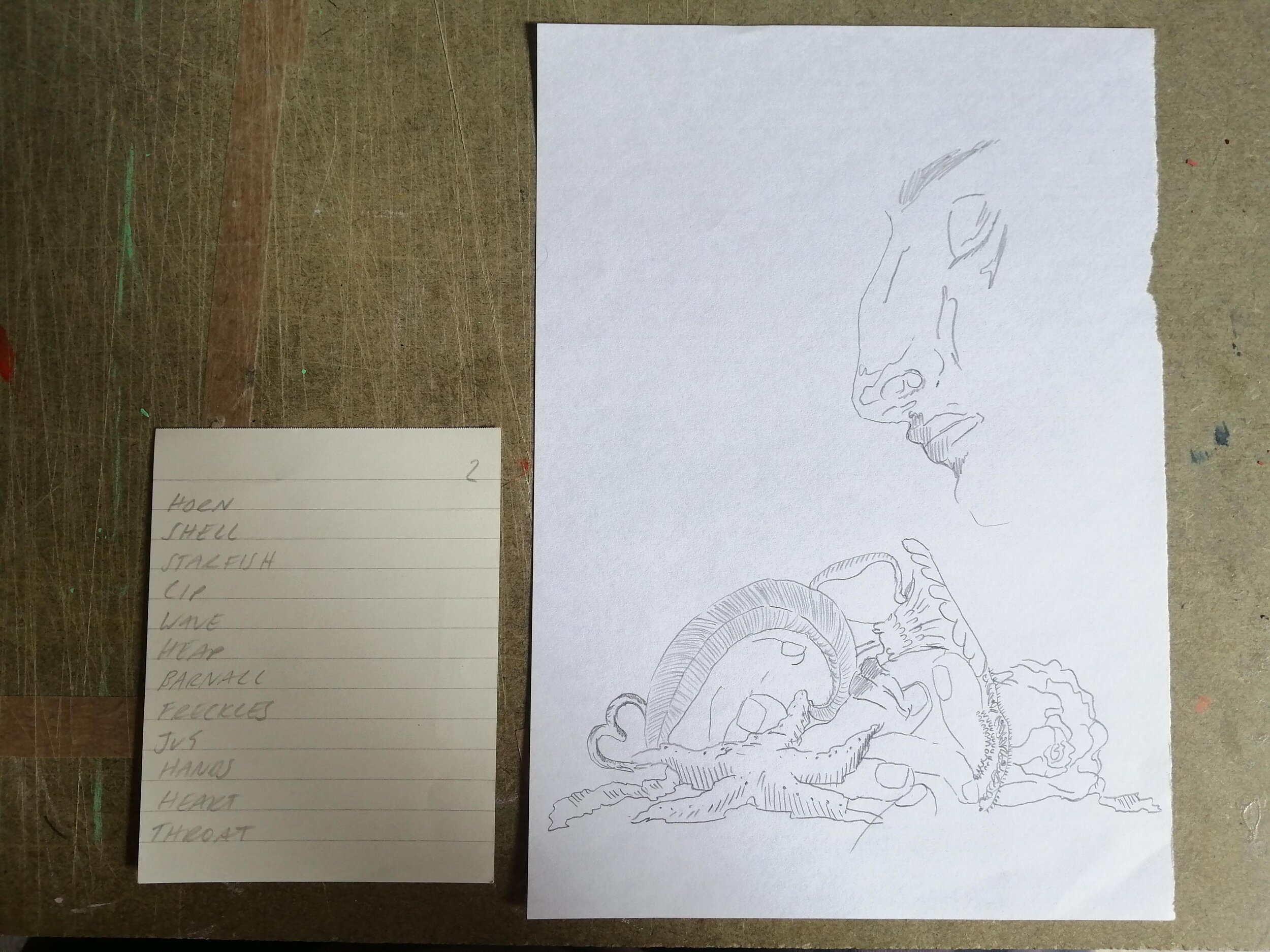

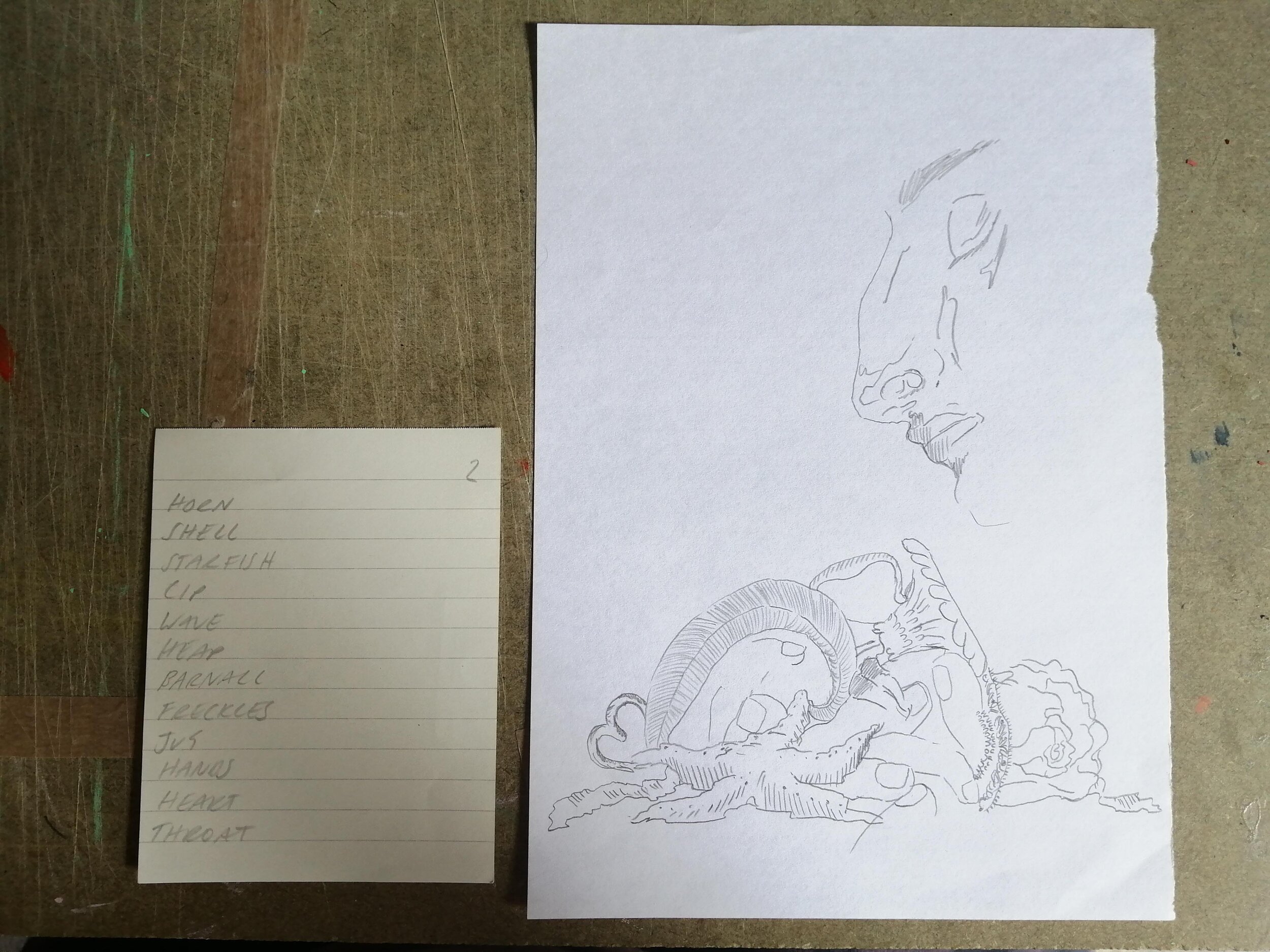

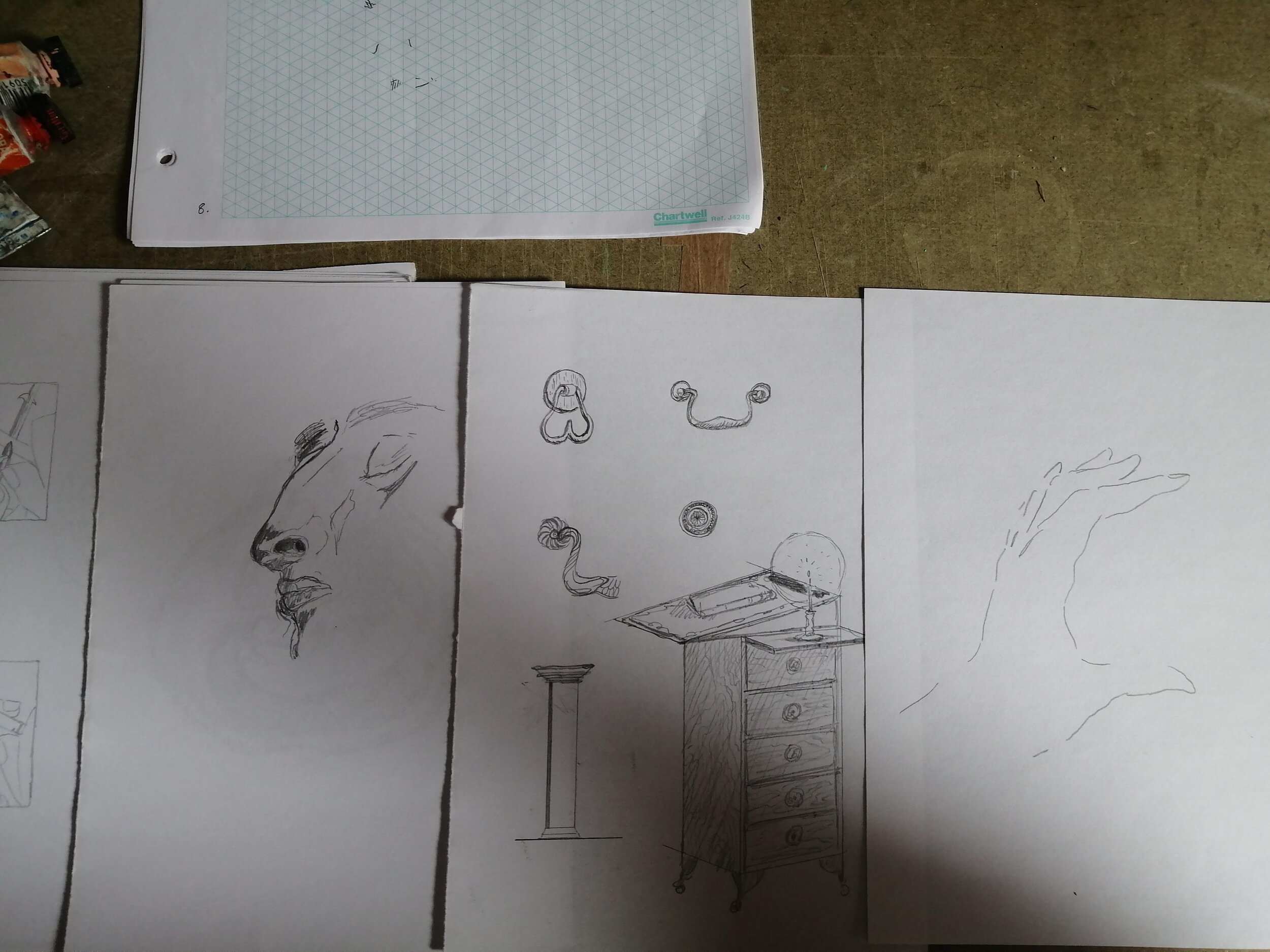

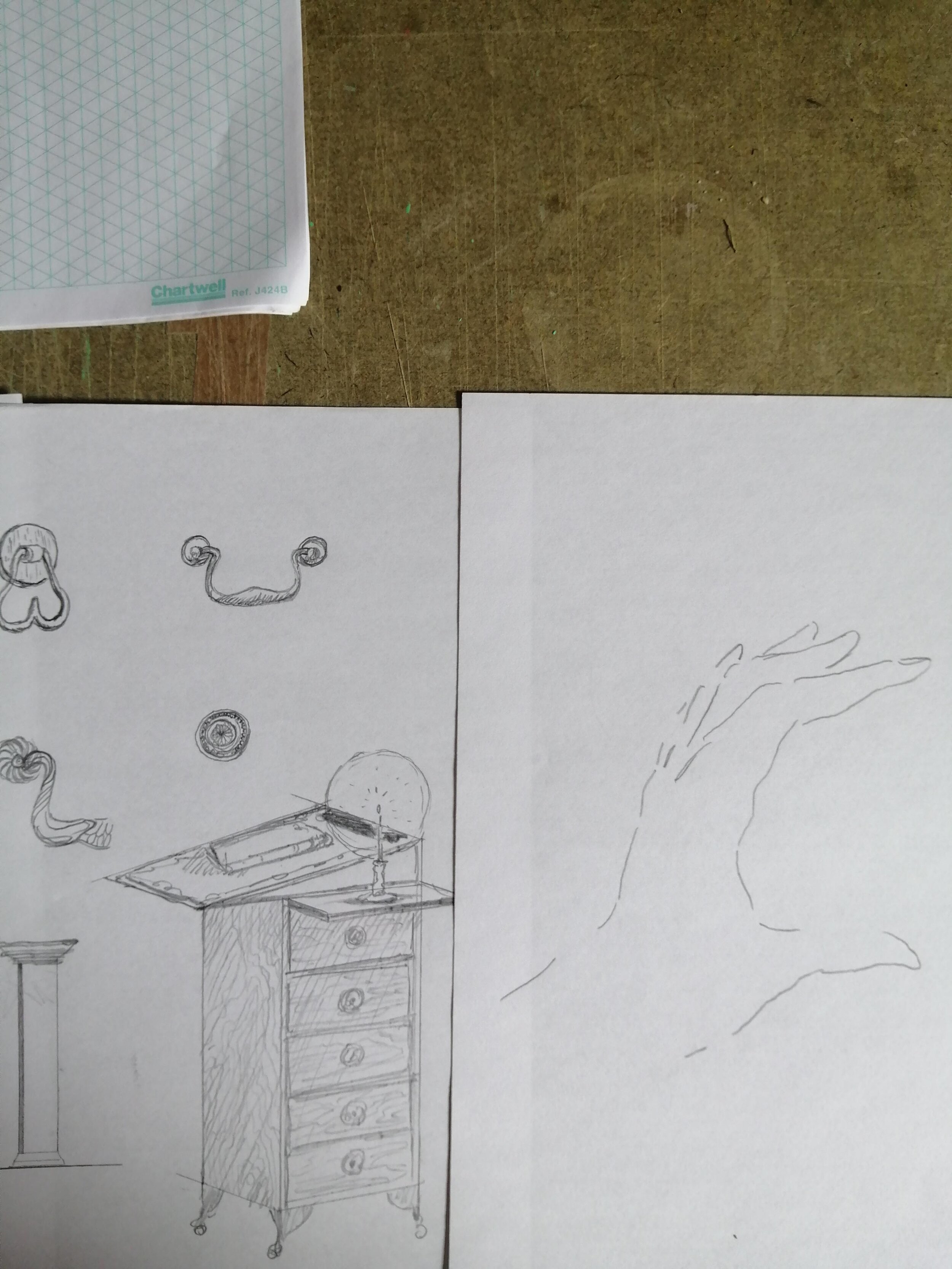

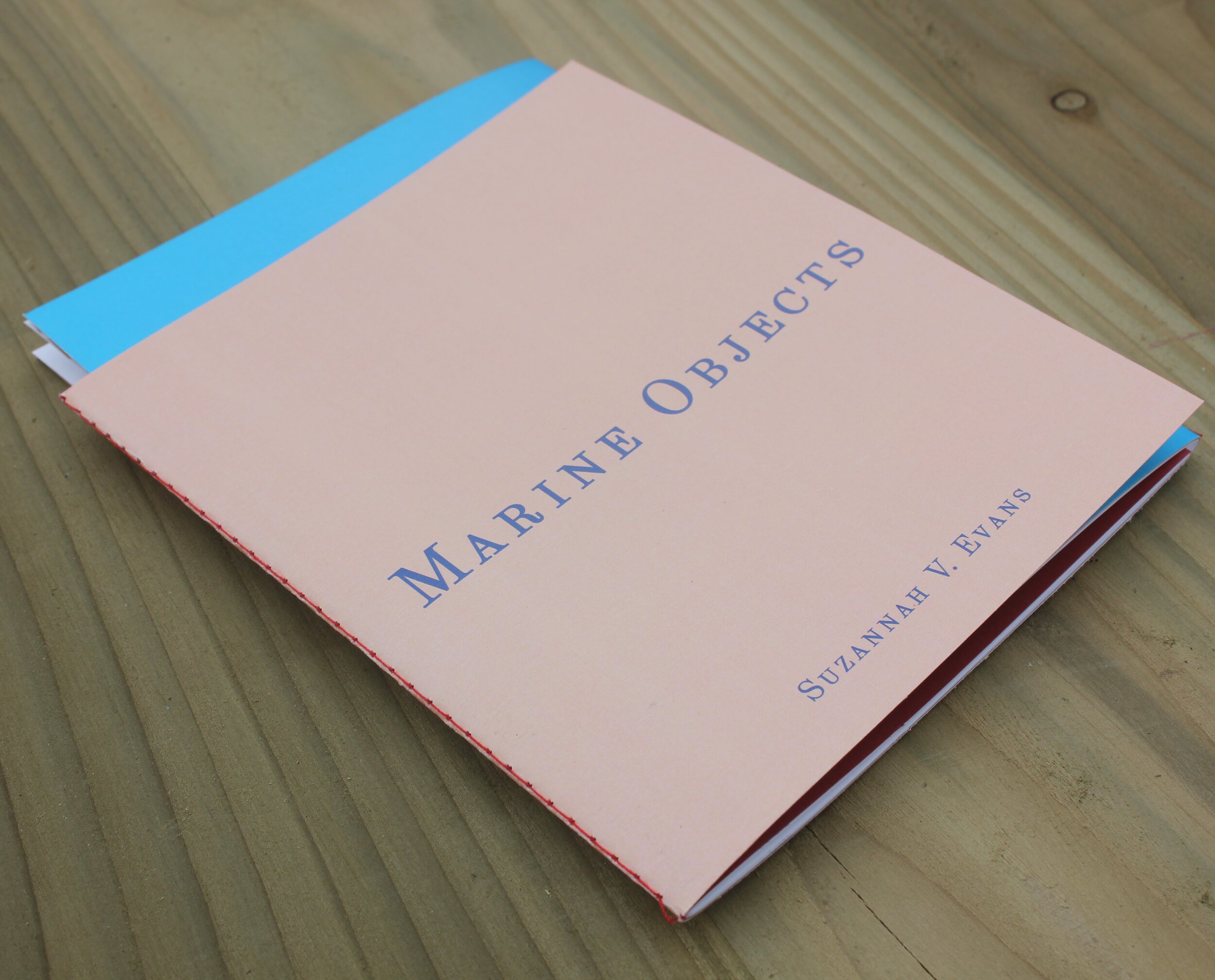

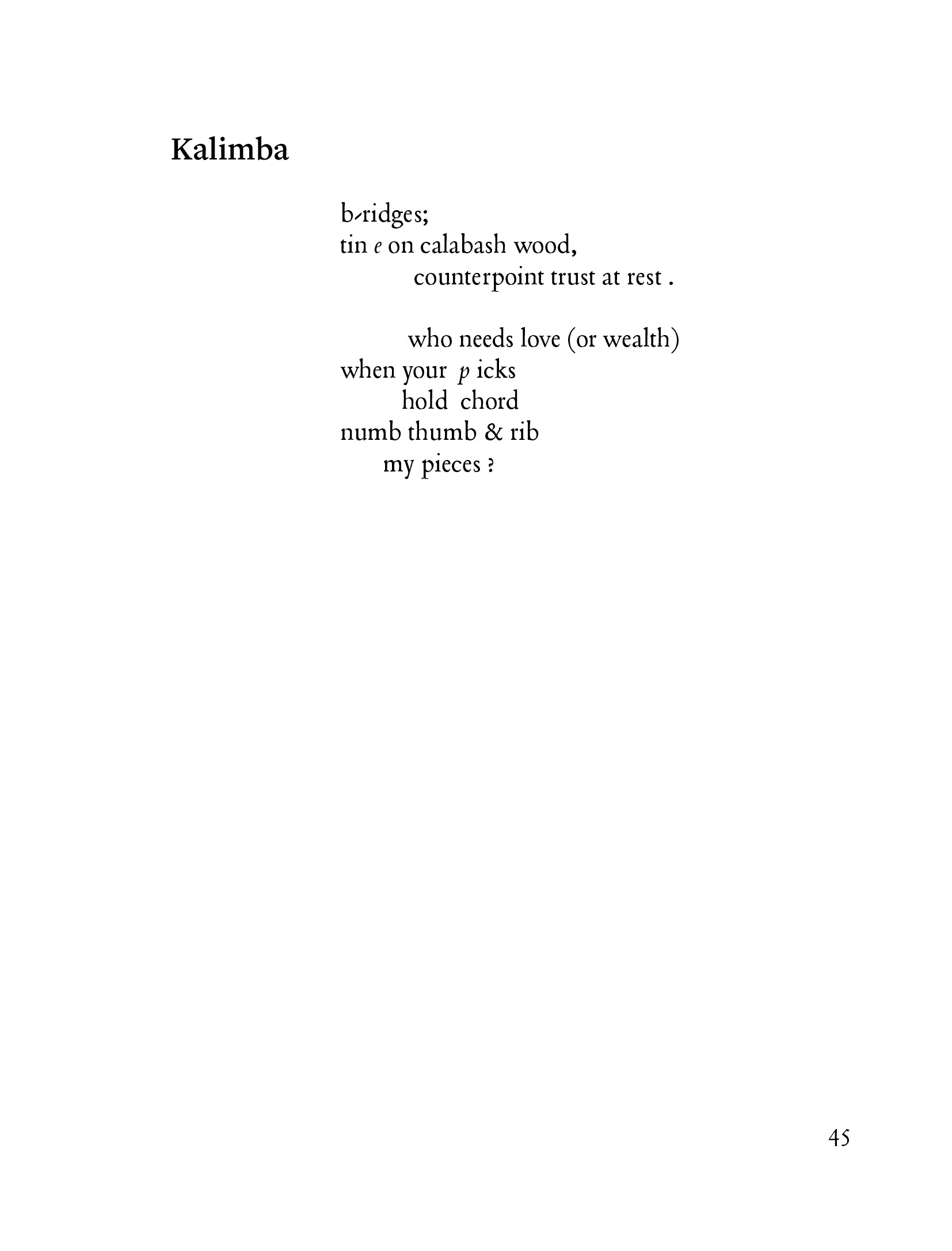

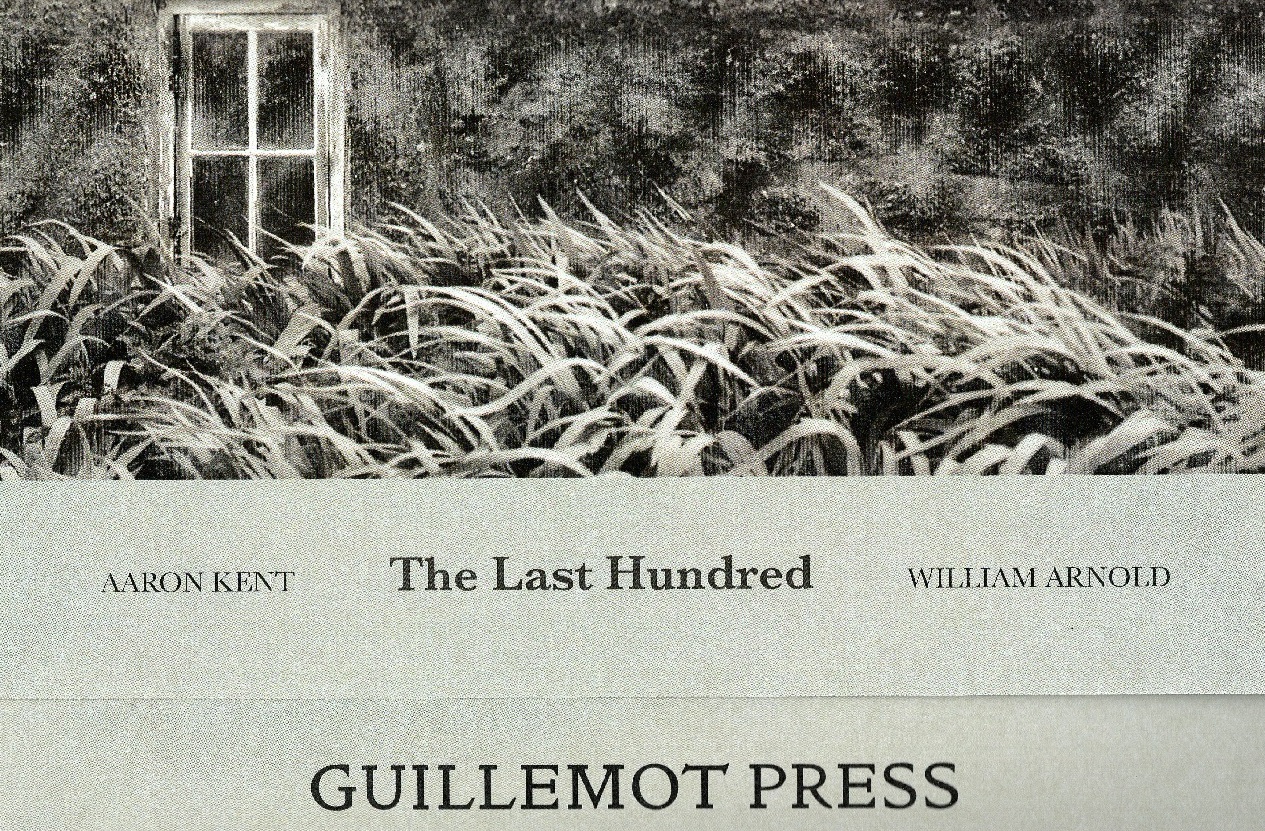

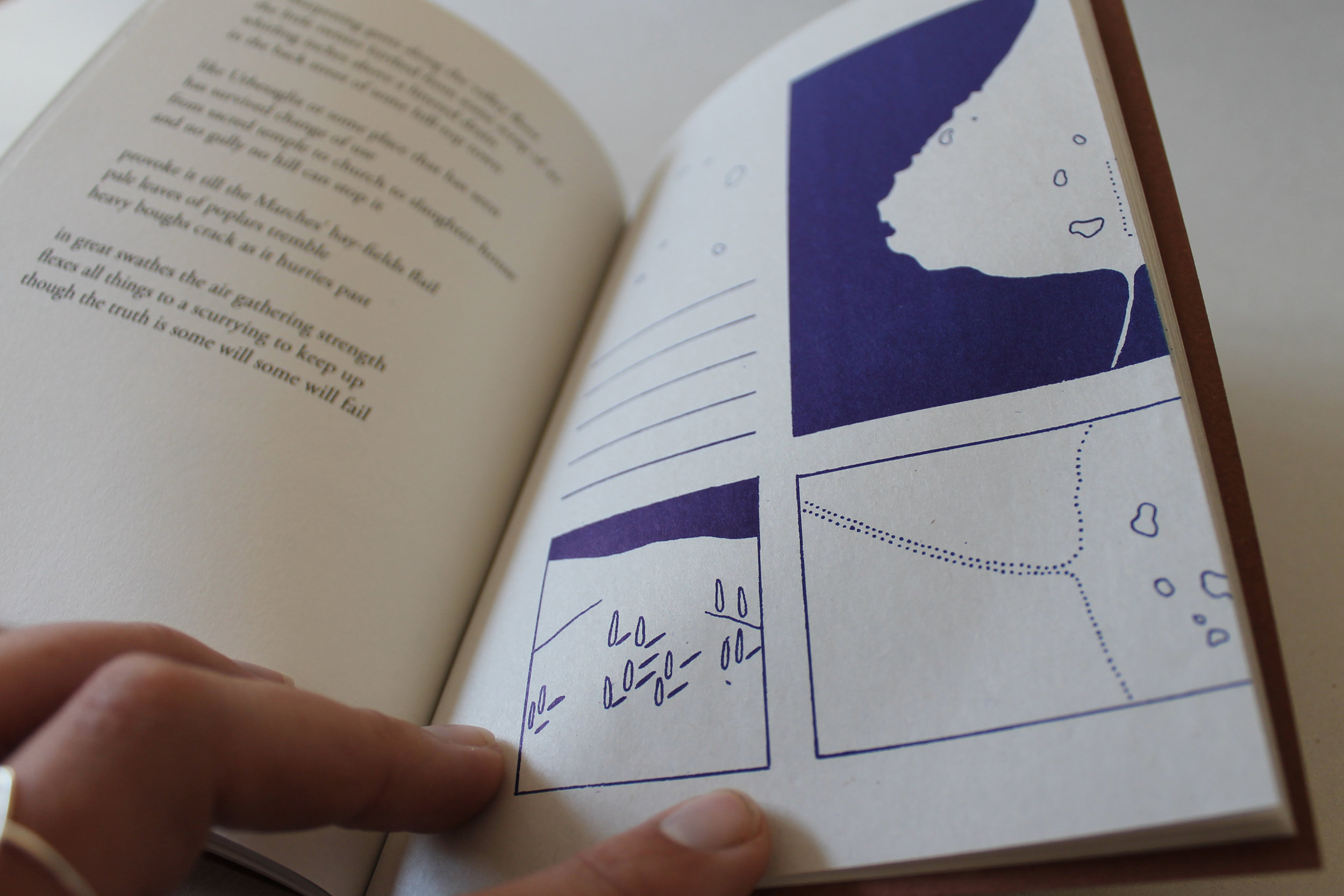

Jen Hadfield is a writer and visual artist based in Shetland. Jen has published three collections, Almanacs (Bloodaxe), Nigh No-Place (Bloodaxe) and Byssus (Picador), which have won prizes including the T.S. Eliot Prize, the Edwin Morgan International Poetry Award, and an Eric Gregory Award. Her fourth collection The Stone Age is due out with Picador in early 2021 and she is currently writing a book of essays about Shetland. Jen has a new 3-pamphlet sequence of writing and painting out soon on Guillemot Press and available for pre-order here.